Bobby’s Blitz Chess

Larry Parr (1946-2011) was editor of Chess Life magazine from 1985-1988 and wrote a number of articles and books about chess. He co-authored The Bobby Fischer I Knew collaborating with Arnold Denker.

Following is one story I remember from the defunct World Chess Network back in 2002 that I enjoyed immensely. It was a story on Bobby Fischer and his blitz prowess. I thought this classic story had been lost, but I found it in the Internet archives when I found a link to my “Bobby’s Blitzkrieg” article had broken.

With all the negativity surrounding Fischer lately, it is always refreshing to get some good news about a man who would make chess an international sensation. The chess world owes a huge debt to Fischer. Get some coffee, tea or something cold to drink and enjoy this one!

by Larry Parr

September 1, 2002

Bobby’s Blitz Chess

There is a conventional wisdom about Bobby Fischer’s development as a blitz player. My view is that this common understanding does not make sense. Not even prima facie sense.

In April 1970, Bobby scored 19-3 (+17 -1 =4) to win the unofficial “Speed Chess Championship of the World,” which was held in Herceg Novi, Yugoslavia. Mikhail Tal (or a Soviet editor in Tal’s name) expressed the common understanding of Fischer as a speed player,

“I don’t know what Petrosian, Korchnoi, Bronstein, and Smyslov counted on before the start of the tournament, but I expected them to be the most probable rivals for the top prizes. Fischer had until recently played fast chess none too strongly. Now much has changed: he is fine at fast chess. His playing is of the same kind as in tournament games: everything is simple, follows a single pattern, logical, and without any spectacular effects. He makes his moves quickly and practically without errors. Throughout the tournament I think he did not lose a whole set of pieces in this way. Fischer’s result is very, very impressive.”

Tal concluded his comments on the blitz championship with the much less quoted, yet significant statement, “We had known, of course, that Fischer is one of the strongest chessplayers in the world. He can defeat Petrosyan, Korchnoi, Spassky, and Larsen. Just as they can defeat him.”

The Herceg Novi blitz event was the speed tournament of the 20th century. It had four world champions competing, and Bobby not only finished 4½ points ahead of Tal in second place, he also obliterated the Soviet contingent, 8½-1½, whitewashing Tal, Tigran Petrosian and Vasily Smyslov, six-zip; breaking even with Viktor Korchnoi; and defeating David Bronstein with a win and draw.

According to one report, Fischer spent no more than 2½ minutes on any game, thereby also giving, in effect, heavy speed odds to powerful opponents. So, while Tal – or a Soviet editor rewriting Tal – is technically correct that the greats could beat Fischer, it is more apt to say that he could beat them far, far more often.

Here is the ever-so-telling tournament table:

EXPLAINING AWAY BOBBY’S DOMINANCE

The problem with Tal’s account of the Herceg Novi tournament is that it offers no explanation for Fischer’s dominance. We are told that “until recently” Fischer “played fast chess none too strongly” but that now “he is fine at fast chess,” an understatement if ever there was one. The conventional wisdom is, then, that there appeared sudden, inexplicable strength where hitherto there had been relative weakness.

On the Internet, inveterate Fischer haters typically argue that Bobby had a good day in Herceg Novi, and the others had a bad day. If – well, if – Bobby had lost a lost position in the first round against Tal, then maybe the final result would have been substantially different. Maybe Bobby would have tanked the tournament. Maybe the next time around Bobby might not prove so dominant. Maybe …. and so on.

“Fischer treats every game as if it were a tournament game, which is why he commits himself totally from the first move to the last even in a blitz tournament.”

~GM Alexei Suetin

Fischer’s chess career has been more minutely dissected than that of any other player, yet we know surprisingly little about his speed playing. True, we know that he won the U.S. Junior Speed Championship in 1957, and we have this reliable testimony of Fischer’s chess teacher Jack Collins:

How strong was Bobby? I remember the 1966-67 New Year’s Eve party at our home. At the time Bobby was competing in and winning his final U. S. Championship. Several grandmasters were present, and there was plenty of eating and drinking. By 2 a.m. Bobby wanted to play some chess, and he had in mind a certain strong international master. But Bobby had drunk quite a bit more than his opponent, and he insisted on playing blindfold blitz chess while the opponent had sight of the board. Still, he won effortlessly.

There are also stories from old Fischer friends about mighty blitzkriegs at the Manhattan Chess Club during the 1950s, and Fischer biographer Frank Brady recalls Bobby giving the GM-strength William Addison pawn and move, while playing him blindfold in blitz. Addison barely broke even! And then there is Bobby’s preposterous score of 21½ – ½ in a strong speed tournament held at the Manhattan Chess Club in August 1971.

All told, Bobby scored 40½-3½ or 92 percent in two major blitz tournaments – Herceg Novi and the Manhattan tournament – against players ranging from strong masters to world champions. Bobby was treating this elite as masters treat class-rated players in simultaneous exhibitions. What Hans Kmoch said about Fischer’s 11-0 sweep in the 1963-64 U.S. Championship – he congratulated second place GM Larry Evans for winning the tournament and Fischer for “winning the exhibition” – could now be said about Fischer’s treatment of world champions and candidates for the world championship.

Let us ponder that titillating total again – 40½-3½ or +38 -1 =5. This tally was not a chance agglomeration of numbers. Many of the games were so good, even though Fischer consciously offered roughly five to two odds in these battles, that Mikhail Tal wrote in a confidential letter to the U.S.S.R. Chess Federation that “Fischer’s lightning games are interesting material for studies” in preparation for Fischer-Spassky I at Reykjavik 1972. He then quoted GM Alexei Suetin as writing, “Fischer treats every game as if it were a tournament game, which is why he commits himself totally from the first move to the last even in a blitz tournament.”

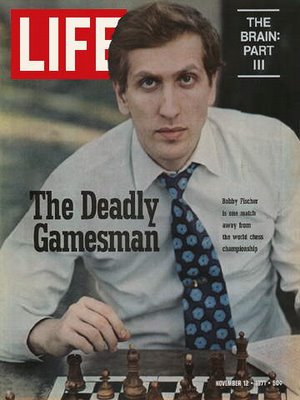

A young Bobby Fischer…

he was said to be a true gentleman at the board.

Clearly, the conventional wisdom that Bobby just got good one year at five minute is ludicrous, if only because he was obviously always exceedingly strong at blitz chess. Such, after all, is what one would expect of, arguably, the greatest natural talent in chess history. Bobby’s only rival in blitz is Jose Capablanca, along with Paul Morphy one of the other two great natural geniuses in chess history.

WHENCE THE WISDOM?

If the conventional wisdom makes little sense and, as we shall see, slyly belittles Fischer’s accomplishments, then the question is whence derives this wisdom? The answer is that it comes from Soviet sources. Articles that appeared in leading Soviet chess journals such as Shakhmaty and 64 were usually regurgitated or summarized in Western chess journals.

To be sure, Bobby’s blitz chess in 1955 was not the same as Bobby’s blitz in 1970. Nor, for that matter, was Bobby’s blitz in 1960 equal to Bobby’s blitz in 1970. Larry Evans recalls, “In 1960 I played a marathon five minute blitz session with Fischer that lasted perhaps three or four hours. We broke even after about 25 games. In 1970, however, I was no longer a match for him at this speed.” There is also a report about the 17-year-old Fischer playing speed chess at the 1960 Leipzig Olympiad, where he dominated the likes of Robert Byrne and Miguel Najdorf but was reportedly still not quite a match for Korchnoi and Tal. More on Leipzig later.

SOVIET COVERAGE OF FISCHER’S BLITZ PLAY

Dmitry Plisetsky and Sergey Voronkov’s Russians Versus Fischer contains some previously classified Soviet chess documents relating to Bobby Fischer as well as material from many articles in Soviet chess magazines. These articles promoted the myth of Fischer as a relatively weak speed player, who inexplicably and miraculously got good. It was also in these articles that great chess men such as Boris Spassky and Tal wrote about Fischer in a tone that was not their own.

Not their own? Am I saying that words that appeared under the names of Spassky, Tal and other grandmasters were invented by others?

After the Piatigorsky Cup in 1966, in which Fischer and Spassky competed famously, the latter said, “It was only after my return to Moscow that I learned that the newspaper Sovietsky Sport had printed an interview with me, in which it was said: ‘During his game with Spassky in the 17th round Fischer asked for the removal from the hall of a woman whose knitting needles, he claimed were disturbing the silence and irritating him.’ …. I must say that I did not see this and, therefore, could not have said anything of the kind.”

“Fischer is too deeply convinced that he is a genius.”

~Mark Taimanov in 1960

Or there is this quotation, supposedly from Tal, about Fischer’s behavior during the 1970 U.S.S.R. vs. The World Match: “Fischer is a child of a different lifestyle than ours, and all his actions are a result of the upbringing he received. But on the whole, he’s not a bad lad, of pleasing appearance, a bit big and slightly awkward, but with a good natured and very winning smile.”

The line about Fischer being “a child of a different lifestyle” (i.e., capitalism) appeared often in the Soviet chess press, but from later interviews with Tal and other Soviet chess personalities, we know that these belittling and condescending attacks on Fischer came from the pens of Soviet editors rather than from the mouths of men such as Tal and Spassky.

One theme in Soviet coverage of Fischer is that his results were miraculous or, as Sovietsky Sport could only splutter about Fischer’s candidates’ shutouts, “A miracle has occurred.” This concept of causation beyond Fischer’s own powers became an important staple of Soviet writing on Fischer, which was meant to deny subtly his status as a unique genius.

.jpg)

“Fischer is too deeply convinced that he is a genius,” wrote Mark Taimanov in 1960, and statements with the same tone often appeared in Soviet chess publications. One of the most egregious was another report by Taimanov (or a Soviet editor) after Fischer lost to Spassky at Siegen 1970. “Even some Americans (whose names I am not going to disclose, being a neutral party) were not too upset by the defeat of their leading player. ‘It’s time Fischer was shown that after all he is not the genius he styles himself to be,’ was their comment.” In the end, however, reality overcame denial. Tal eventually stated straight out that Fischer was “the greatest genius to have descended from the chessic sky.”

In 1958 the 15-year-old Fischer visited Moscow along with his sister. Yuri Averbakh has described how the U.S. Champion played lightning games at the Central Chess Club, apparently mopping the board with such young comers as Yevgeny Vasyukov and Alexander Nikitin. In 1971, directly after the Fischer-Taimanov match, Bobby would astonish Vasyukov by recalling his games against him from memory. More on this feat below.

In Moscow in 1958, Bobby wanted to do more than play the young comers. He wanted to play against the Soviet world champion and the cream of the imposing Soviet grandmasteriat.

Tigran Petrosian – or a Soviet editor inventing comments from Petrosian – afterwards claimed, “I was the person summoned to the Club to ‘cope’ with a youth who was beating the Moscow masters at lightning chess.” How well he coped with Fischer remains unclear. Fischer biographer Frank Brady claims that Bobby won some games from Petrosian, who had already twice been a candidate for the world title. If the match were at all close, then Petrosian did not “cope” well with a 15-year-old.

Indeed, one suspects that Fischer scored excellently in Moscow. Here is a revealing passage from GM Mark Taimanov’s memoirs:

[Fischer’s] memory was amazing. Just one more example. It happened in Vancouver, Canada in 1971. At the closing of my infamous match against Fischer, Fischer and I were sitting with fellow grandmasters at a banquet and were talking peaceably after the preceding storms …. The conversation revolved around the match until my second, Yevgeny Vasyukov, suddenly turned to Fischer:

“Bobby, do you remember that in 1958 you spent several days in Moscow and played many blitz games against our chessplayers? I was one of your partners.”

“Of course, I remember,” Fischer replied.

“And the result?” Vasyukov asked.

“Why only the result?” Fischer responded. “I remember the games. One was French.”

And he rattled off all the moves

There is nothing discreditable to Fischer in the above. Far from it, in fact. Yet the conversation between Vasyukov and Fischer does not ring true. Fischer would almost certainly have answered the question about his results, and Taimanov does not choose to fill in the blank. The logical supposition is that Bobby scored very well in blitz back in 1958.

At Mar del Plata 1960, Fischer and Boris Spassky buried the other competitors under the Argentine pampas by sharing first prize with the score of 13½-1½. Spassky wrote a report on the tournament. “Bobby is capable of playing chess at any time of the day or night,” he or a Soviet editor wrote. “He can often be seen playing lightning games after a fatiguing evening session of adjournment play. The US Champion plays lightning games with pleasure and, indeed, with a gusto. The only thing that displeases him in chess is – losing. In such cases the pieces are instantly set up again, for a revenge. Failure to take revenge noticeably upsets Fischer. He responds to moves hurriedly and, in an effort to calm himself, keeps repeating that he has an easily won position.” Spassky also supposedly put in a plug for Soviet chess literature by claiming that Bobby immersed himself in the stuff. “On one occasion,” it is claimed, “he noticed a bulletin of the latest USSR Championship. This brought a glint to his eyes, and he exclaimed, ‘That’s just what I need!’ He asked permission to take the bulletin and immediately vanished. Fischer is one of the most diligent readers of our chess magazines. He always follows which of his games are published in our press.”

Nothing in the above is implausible. What stretches credulity is that Spassky wrote much of it. The tone is not his. The snide reference to Fischer’s reaction to losing (without ever claiming that he actually lost many blitz games in Mar del Plata) does not sound like Spassky. Moreover, expending lots of words about Bobby’s regard for Soviet publications is definitely not Spassky.

Here is how Yugoslav journalist Dmitrije Bjelica portrayed a blitz encounter between Tal and Fischer at the 1960 Leipzig Olympiad, an account that appeared in the Soviet chess press:

Fischer was in the limelight at the Olympiad. Tal was late in arriving, and Bobby kept asking when the world champion was coming. “Maybe Tal doesn’t want to play me? He scored four wins against me in the Candidates’ Tournament and is now afraid of a revenge!”

But Tal did come. And although he was tired after his journey he couldn’t refuse Fischer a few lightning games. They played five games, and Tal won 4:1. But Bobby, contrary to his custom, didn’t get angry because Tal promptly crushed Najdorf too, who had very much angered Bobby.

This is what happened. Najdorf had asked Fischer for an autograph. Bobby had agreed, but – for one dollar. This had offended Najdorf. Then came their game in the Olympiad. Bobby had an easily won game but made a mistake, and Najdorf was able to draw. Bobby then swept the pieces off the board in disgust, and Najdorf merely said:

“You’ll never play in South America again ….”

The picture that Bjelica paints is a Portrait of Dorian Bobby. I do not believe that Fischer said, “He [Tal] scored four wins against me in the Candidates’ Tournament and is now afraid of a revenge!” There is the unEnglish “a” in front of “revenge,” and there is the stilted diction of Bobby dully, mechanically reciting that Tal beat him four-zip in the 1959 Candidates’. There is also the claim that Bobby “swept the pieces off the board” against Najdorf and usually became angry when dropping blitz games. Spassky made no such claim when covering Mar del Plata 1960, and Tal would later aver forcefully, “It is also important to remember that he [Fischer] was a real chess gentleman during games. He was always very fair and very correct.”

In less than 10 minutes Fischer had lost the first game. He lost the second one even faster. Geller was laughing so that there were tears in his eyes.

~story of a clueless Fischer after being fed to the legendary Leonid Stein by Efim Geller

BUT: the biggest problem with Bjelica’s account is that it is against the laws of both Newtonian and Einsteinian physics! Bjelica has Tal and Fischer playing each other directly after Tal’s arrival at the Leipzig Olympiad, the first round of which was played on October 17, 1960. Bjelica then claims that Tal scored 4-1 but that Bobby did not become angry because Tal “promptly” beat Najdorf with whom Fischer was enraged because of the above mentioned autograph dispute and their game in the Olympiad. Yet that game was not played until November 4, 1960, more than two weeks after the Fischer-Tal blitz match!

Did Tal actually beat Fischer 4-1? Were there, perhaps, other speed sessions between the two chess greats in which Fischer triumphed? Hard to say. But what can be asserted is that Bjelica’s reporting, which appeared in the Soviet press, cannot be relied upon.

Bobby Fischer’s first utterly stunning triumph was Stockholm 1962, the interzonal tournament in which he scored 17½ – 4½ to finish 2½ points ahead of a field with four top Soviet grandmasters. Soviet reporting credited Fischer with a remarkable performance, but there were also the usual effusions directed against his person.

Efim Lazarev, the biographer of GM Leonid Stein, tells the following story about a speed session between Fischer and the Soviet grandmaster the night after the first round at Stockholm:

That evening, after the round, Stein came to see Geller. Fischer too dropped in. In his halting Russian he suggested a lightning chess match with Geller. Geller was clearly in a bad mood that evening [after losing to an unheralded Colombian IM], but, on hearing the offer, could not restrain a sly grin and, pointing to Stein, who was sitting modestly in a corner, said:

“Play him instead.”

Since Fischer had not been present at the drawing of lots and Stein had not played in the first round, the American was not acquainted with him. Geller introduced them. At first Bobby declined to play someone whom he took for a novice, someone who clearly could not be a worthy opponent at lightning chess. However, then he agreed to play Mr. Stein but added that he would not play for nothing …. Bobby proposed a small stake: 10 crowns. To equalize their chances, he offered Mr. Stein a handicap: if Mr. Stein won even two points in five games, the stake would be his.

“Very well,” Stein replied.

In less than 10 minutes Fischer had lost the first game. He lost the second one even faster …. Geller was laughing so that there were tears in his eyes.

The outcome surprised Fischer so that he now proposed playing on equal terms.

With much greater respect for the newcomer, he now began playing less rashly but still failed to secure an advantage. In the evenings that followed, Bobby often invited Stein, with whom he had become friendly, to new lightning chess encounters, in which first one and then the other would emerge the winner.

The above account by Lazarev, wafts with ichthyological perfume.

- First, Bobby would have known the names of his opponents in the interzonal and would have prepared for games against every single one, including even those trailing in the caboose of the tournament table.

- Secondly, the author has Bobby addressing GM Stein as Mr. Stein, and the idea that he would not associate the two names is absurd.

- Thirdly, everyone is agreed that Bobby read chess literature voluminously with nearly total recall, and Stein’s picture had appeared in numerous magazines by 1962.

- Fourthly, after supposedly losing a speed match to Stein, the author still has Bobby regarding him as a “newcomer” rather than the strong grandmaster whom Bobby surely recognized from the very beginning or, at the very latest, after the first game between them.

- Finally, the author speaks of further chess encounters during succeeding evenings, claiming that “first one and then the other would emerge the winner.” This last phrase is meaningless, and we have no idea what the real balance of the results might have been.

After 1962, Soviet reporting on Fischer’s speed play falls off. There is mention of an offhand game between Fischer and Stein at Havana 1966, but not much more than that. Perhaps, the common sense conclusions – which ought to be the conventional wisdom – are the following:

- Earlier Soviet reporting exaggerated Fischer’s problems in speed play as a ploy to imply that he was not a chess genius nonpareil;

- By the mid-1960s (as suggested by the testimony of Jack Collins, Frank Brady and others), Fischer had become utterly formidable in five-minute chess; and

- The Soviets stopped writing on Fischer’s speed play because horror stories about Bobby rolling Soviet grandmasters were unwelcome in the pages of 64 and Shakhmaty.

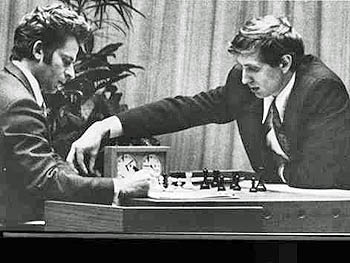

I really liked the article. A small point, though: the last picture is not Fischer and Spassky at the 1972 World Championship.

You’re right… wrong picture.

GREAT ARTICLE. SO MANY CHESS PLAYERS IN RECENT YEARS TALK SO MUCH HYPE ABOUT THE MODERN PLAYERS, BUT IN REALITY, I DO NOT SEE ANY FISCHER’S OR TAL’S! JUST A BUNCH OF PAWN WRESTLING POSERS! LOL

I agree Mick! Fischer was able to do thing his own way and prove that sometimes two heads (or more) are not better than one! He did so much for chess and the media is slowly undoing this with all these negative stories. It’s a shame.

TO ME IT WAS OBVIOUS THAT FISCHER HAD A TYPE OF UNTREATED SCHIZOPHRENIA, AND THIS LEAD TO HIM DISAPPEARING AND DOING THINGS HE OTHERWISE WOULDN’T HAVE DONE. IF THIS COULD BE ESTABLISHED, AND THE FACT HE RAISED HIMSELF AND WAS SINGLE MINDED TO CHESS, THEN PERHAPS PEOPLE WOULD NOT BLAME HIM SO MUCH FOR A FEW WRONG WORDS? AS FAR AS HIM BEING THE BEST PLAYER OF ALL TIME, NO ONE HAS EVER DOMINATED THEIR PEERS AS MUCH AS FISCHER DID. MY GUESS FISCHER’S REAL RATING WOULD BE OFF THE CHARTS TODAY!

I am not sure on that diagnosis although many (including a few professionals) have given their views. I also believe there are some people defaming Bobby posthumously because of his hateful rhetoric. I feel the current negativity in the news place too much emphasis on the mental instability. He originally known as an embattled and embittered man… and he was exploited by many.

He disappeared into Asia and Eastern Europe after 1975 resurfacing only to make new pronouncements in chess (i.e., Fischer Random, prearranged games, political statements). From 1975-1992, were saying he was unstable. His acrid radio interviews from the Philippines, his hatred of Jews and his paranoia in thinking that the U.S. government was after him started an examination of his mental state.

After playing in Fischer-Spassky 1992, he was threatened with arrest for violating a U.S. ban for travel to Yugoslavia. His comments on 9/11 were probably the final blow. He is not the first to have any of these thoughts. His imprisonment in Japan was shameful and it was the culmination of his battle.

Here is the other side. See these interesting photos!

https://www.thechessdrum.net/blog/2009/10/14/rare-bobby-fischer-images/

Thank you.

I think as stated above on B.F visit to Moscow he beat up the masters, then as in a biography by Frank Brady? It is said they sent Stein to beat Fischer. SO he must have known him.

Not sure. Maybe the Soviets decided to send Stein after learning about their blitz matches. Stein was a brilliant player and they may have realized that he could pose problems.

DAAIM thanks for keeping us chessplayers inform on whats new in

the chess world….

A fascinating account. What actual records are there of Bobby’s blitz games – eg at Herceg Novi ? Or was it simply not possible to record blitz games in the pre-computer era?

I don’t believe any of the games were record except from memory. Fischer was legendary for his prodigious memory. I haven’t checked his collected games, but I would not be surprised if he wrote down all of his games from memory.

I realize I’m three years late for this email chain, but I couldn’t help joining it. In an interview quoted on this website (https://www.chessintranslation.com/2011/03/anti-hero-evgeny-vasiukov-on-viktor-korchnoi/), Yevgeny Vasiukov claims:

“… on his arrival in Moscow [in 1958], Fischer said that he only wanted to play Botvinnik. That made a lot of people smile, as Mikhail Moiseyevich stood on such a pedestal, and the idea that he would simply play a training game against someone (and an American at that) was inconceivable. For the two weeks that Fischer was in Moscow he played blitz from morning to night, and gave everyone an incredible battering. And then three people were invited, based on the results of the most recent “Vechernaya Moskva” blitz tournament, which was the unofficial Soviet Union blitz championship. They invited the three winners: Petrosian, who came third, Bronstein, who lost a match to me for first place, and myself. But David Ionovich [Bronstein], who had already played a World Championship match, said: sorry, but why should I play a kid? Tigran Vartanovich [Petrosian] and I arrived. We played in the grandmasters’ room, and Petrosian won by a small margin, while I literally crushed Fischer. From that point on whenever we met he always treated me with great respect.”

oh Nice Post never seen this before however as an Ultramodernist i find it difficult if not impossible for a Traditioanlist to “CRUSH” an Ultramodern Chess Player such as Fisher, basically becuz ur too far behind in CHESS.

I’ve read this. “Bobby Fischer Goes to War” maybe?

WOW! Thanks Daaim that sound amazing ill check with the Buffalo Public Library and see if they have that book! The Traditional chess players were so far behind Fisher and hes so competitive even when he plays bullet chess that i just dont see how they could possibly do that back then and even now with some of these gms on the Icc, im told they over there movin that knight everywhere is that true?

Neil Parker in the book Russians versus Fischer by Dmitry Plisetsky and Sergey Voronkov 2005 there are 12 games from the World Blitz Championship Herceg Novi April 8 1970 starting on page 182 . 12? Fischer games. In the book there are all of Fischer’s games with Boris spassky. 30. It includes archives from the KGB, the Communist Party Central Committee, and the USSR sports committee.. Neil you may also go on the website http://www.chessgames.com. I hope I was helpful. Check out the book. It’s all about all the Soviet Grandmasters notes on how to beat Bobby Fischer. Maybe not all the notes.