Lateral Thinking in Chess

by Mark Bowen (Kingston, Jamaica, WEST INDIES)

Prior to the start of the 1998 Winter Olympics at Nagano, the World Powers in Ice Hockey were considered to be the USA, Canada, and Russia. Facing these daunting opponents the Czech Republic team adopted an unexpected defensive approach. The Czechs had only one big name player, their goalkeeper Dominik Hašek (pictured right), and they built their game plan around him. The strategy bamboozled their aggressive minded opponents. The Czech Republic took Gold.

Two years later and we find the most successful player in the history of Chess, Garry Kasparov, surprisingly beaten by his former pupil Vladimir Kramnik for the Championship of the World. Kasparov loses because he is unable to crack the solid and previously unheralded Berlin Defence of the Ruy Lopez. Interviews with Kramnik later reveal that his match strategy was influenced by the Czech Ice Hockey team.

Yes, lateral thinking works in chess, and not just at the stratospheric level of Kramnik and Kasparov. There are some problems which cannot be solved easily without thinking laterally. Are you ready to use lateral thinking to improve your Chess ?

Edward de Bono, (the man who coined the term “Lateral Thinking “), once said:

“Lateral thinking is like the reverse gear in the car. One would never try to drive along in reverse gear the whole time. On the other hand, one needs to have it and to know how to use it for maneuverability and to get out of a blind alley.”

Your lateral thinking skills will complement the more conventional thinking methods, giving you that, much needed, secret edge to win more. Reading widely in areas apparently unrelated to Chess, is a good way to jump start your creativity. Strategic thinking can be developed by learning more about nature’s predators, other sports and military strategy.

Understanding human nature generally, through psychology and literature, as well as history, may also help tremendously. Study whatever areas interest you personally, and then spend time reflecting, on how the principles in your favourite areas, may apply to a Chess game. There is no limit to the connections you can make. Anything at all can be related back to chess. Bobby Fischer himself said “Chess is Life” and both Viktor Korchnoi and Anatoly Karpov had books with similar titles also. Use your life lessons in your chess game. Make your personality flourish on the board.

How do you approach the game? For some Chess is the Martial Art of the Mind. (Grandmaster Maurice Ashley admits to using his knowledge of Aikido and Energy on the chess board also.) Some see it as a science, some as a sport, some like Emmanuel Lasker, view Chess as a fight. “Chess is a Language,” say some fluent players. Realize that your outlook will affect how you play the game and find the approach that works best for you. Try on different approaches. Bent Larsen viewed chess as, “a beautiful mistress.” This lateral (or some may say horizontal) thinking no doubt helped his enjoyment of the game tremendously.

“Predators, which I personally enjoyed learning about, include the Jellyfish and the Crocodile, their methods can also be applied to chess.”

Next time you need to beat a player, to get more rating points, think of yourself as a predator, looking for lunch, and see what ideas come to you. That’s what Simon Webb did in his excellent book Chess for Tigers. Predators, which I personally enjoyed learning about, include the Jellyfish and the Crocodile, their methods can also be applied to chess. Tune in to the Discovery channel and watch the Super Nature series.

Chess for Tigers is basically a chess version of the classic Book of Five Rings written by the legendary swordsman Musashi. The basic premise of both books is Know Yourself, Know your Opponent, Use Prevailing conditions to your advantage and have relentless dedication to constantly improve. The Art of War by Sun Tzu is another example of this philosophy. All three of these books will help develop your lateral thinking in a strategic way.

While some gain insight from the dominating methods of Niccolo Machiavelli and Otto von Bismarck in political history, others use literature to develop their chess. Jonathan Rowson’s book on the Seven Deadly Sins of Chess is replete with literary references. Mark Dvoretsky, the leading chess trainer of Russia, quotes readily from classical literature, and also from famous chess players, in his profound books. Perhaps it is their broad educational system, and knowledge of history, that has been the real source of the Soviet success in Chess. If you don’t know who Vladimir Nabakov is then at least play some Bob Marley music and remember that, “If you know your history, then you would know where you’re coming from.”

The January 2002 issue of Chess Life has the following example of lateral thinking in Chess. After a game in which a lone knight holds off two black passed pawns, allowing white time to promote his own pawns and win narrowly, the winner, Miles Kinney, said he got the idea from the historical story of Horatius. Apparently, the heroics of the Roman senator, who lost his own life while single handedly delaying an enemy advance against the only bridge into Rome, had inspired his winning strategy.

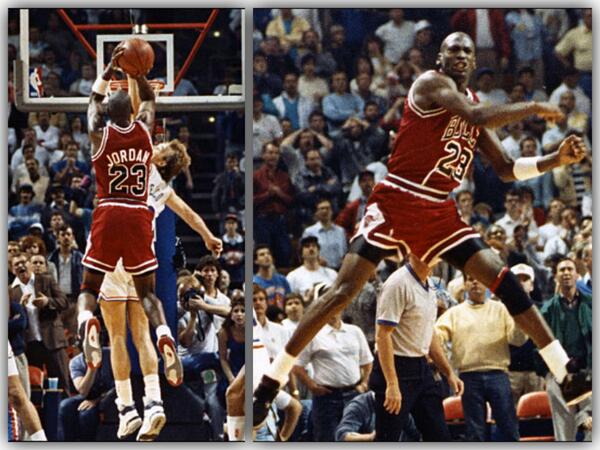

Michael Jordan was a quintessential lateral thinker.

Photo by Ed Wagner Jr. (Chicago Tribune)

Modern fiction can inspire ideas also, a scene from a book in the Kane’s War series describes a chess match as follows:

“Kane slid quietly into something he’d seen once at a game in New York. Guy there had called it the “No-Name Defense”. Said he’d evolved it after studying the ancient Chinese military strategist, Sun Tzu.”

Here the author, Nick Stone, has cleverly blended in an element of American Football with Chess and Oriental Military Stratagems. The No-Name Defense is legendary for bringing victory to the Miami Dolphins in the early seventies.

Studying other sports (as Kramnik did with ice hockey) is a very effective way to gain insights. Many chess players, including the great Boris Spassky, find Tennis particularly interesting. The use of the serve is similar to the use of White pieces for instance. Do you have a favourite Soccer team ? Perhaps you could use their approach on the chess board also. What about your favourite players? Wouldn’t it be great to play chess the way Michael Jordan plays basketball? Think about it and see if it helps your creativity.

The Latvian Mikhail Tal is known to be one of the most creative players of all time. He described his thoughts just before making a knight sac in a game, against Evgeny Vasiukov (USSR Ch, Kiev, 1965), thusly:

“The sacrifice was not altogether obvious, and there was a large number of possible variations, but when I conscientiously began to work through them, I found, to my horror, that nothing would come of it. Ideas piled up one after another. I would transport a subtle reply by my opponent, which worked in one case, to another situation where it would naturally prove to be quite useless.

As a result my head became filled with a completely chaotic pile of all sorts of moves, and the famous ‘tree of the variations’, from which the trainers recommend that you cut off the small branches, in this case spread with unbelievable rapidity.

And then suddenly, for some reason, I remembered the classic couplet by Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky:

“Oh, what a difficult job it was

To drag out of the marsh the hippopotamus.”I don’t know from what associations the hippopotamus got onto the chessboard, but although the spectators were convinced that I was continuing to study the position, I, despite my humanitarian education, was trying at this time to work out: just how would you drag a hippopotamus out of the marsh? I remember how jacks figured in my thoughts, as well as levers, helicopters, and even a rope ladder.

After a lengthy consideration I admitted defeat as an engineer, and thought spitefully: ‘Well, let it drown!’ And suddenly the hippopotamus disappeared going off the chessboard just as he had come on. Of his own accord! And straightaway the position did not appear to be so complicated. Now I somehow realized that it was not possible to calculate all the variations, and that the knight sacrifice was, by its very nature, purely intuitive. And since it promised an interesting game, I could not refrain from making it.

And the following day, it was with pleasure that I read in the paper how Mikhail Tal, after carefully thinking over the position for 40 minutes, made an accurately calculated piece sacrifice…”

Use Lateral Thinking in Chess like the sword Alexander used to cut the proverbial Gordian Knot. Lateral Thinking, like chess itself, is not mastered in a day, but then nothing worthwhile ever is. Hopefully this article has served as “a finger pointing to the moon” of Creativity. (Speaking of the moon, did you check your horoscope today? You should because some players swear that even a knowledge of Astrology helps their chess.) Lateral thinking is a helpful tool to anyone seeking to improve their Chess.

Try it.

Written and copyrighted

by Mark J.B. Bowen

Saturday, March 30, 2002