Historic Moments: DC/Maryland Legends

Most large cities in America have some type of a chess tradition. It is interesting to travel to another city and hear about the “local legend,” or the player in town that everyone is in awe of. Granted, on the national stage, this person fails to register so much as a blip on the chess radar screen, but they find fame and fortune at home. In cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Berkeley, Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia to name a few, legends are more prominent.

One area with a rich chess history, particularly in the Black community, is DC/Maryland. Of course, Maryland native Theophilus Thompson, the first Black player of note. He wrote a famous book of chess compositions titled, “Chess Problems: Either to Play and Mate.” One hundred years after his birth, he could not have dreamt that a place such as “Dupont Circle” could be synonymous with the game he loved.

You may have gotten a glimpse of the Dupont Circle chess culture in “The Emperor of Ocean Park,” a mystery novel which was based on intricate chess themes. In this book, author Stephen Carter writes of a character named “Talcott” whose efforts to solve a murder mystery takes him through Dupont Circle. This “real live” place has a history of its own, but a bit less fabled than New York’s Washington Square Park.

The chess tables at Dupont Circle were built in 1968 and the playing venue was recently the subject of an article in the American University student paper. All of these places (i.e., Chicago’s Harper Court, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, Santa Monica Beach) have an indelible impression in the annals of chess history and in the passing of time, we recollect stories, names and offhand comments. “Remember when so-and-so came to DuPont Circle?” someone may state. Some of the names mentioned in the DC/Maryland area may not be well-known anymore, but in the turbulent 60s, DC/Maryland was perhaps the crown jewel of Black chess talent.

Walter Harris: America’s First Black Master

More than 100 years from the birth of Thompson came America’s 1st Black master in Walter Harris. Harris, originally from New York, was an accomplished player at the scholastic level playing in at least one U.S. Junior Championship in 1959 where he placed 5th (of 40 entrants). He also scored 7-5 in the concurrent U.S. Open and won a prize for the top “Class A” player. (See chart below)

Sometime thereafter, Harris entered the U.S. Air Force played put his skills on display and played in the Armed Forces Chess Championships. Harris also spent time on the west coast and became the story of legend at UCLA. Daniel Van Arsdale, wrote about one day in particular:

I was a math major at UCLA from 1963-67, and used to play a lot of chess (once had a 2137 USCF rating). I had read about Harris, and once he showed up at UCLA, at a room where the chess was played. Someone told me (later) who he was, and we played a five minute game. I just happened to win the first game, but Harris slaughtered me in the remaining games, about 15 as I recall!

Apparently, Harris had settled in Washington, DC taking a position as a scientist in the U.S. Naval Observatory. Gregory Kearse, who wrote a seminal article on Black Masters for Chess Life described the scene in DC and emergence of Harris.

“In 1963, America was on the verge of a cultural explosion that would touch our lives and alter its very social fabric. Even in the world of chess, with its then exclusive clubs and its odd assortment of esoteric warriors, a minor revolution had taken place. America produced its first black chess master. His name was Walt Harris, an unassuming, dedicated scientist who for some years worked at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., the nation’s capitol and a strong urban chess center.”

Legends will Follow

During this time, chess was booming in the DC/Maryland area and it was bolstered by three players in particular. Kenneth Clayton, Frank Street, Jr. and later Charles Covington. Clayton 1963 Amateur Championship preceding his protégé Street by two years. He became a Master in 1967 and Kearse states, “In his chess prime, Ken Clayton would take on all challengers in addition to tutoring at the Benjamin Banneker Recreation Center, across the street from the historic campus of Howard University.”

Covington described their rivalry as consisting of many games in which Clayton “usually came out a little ahead of me.” In the late 70s, Anatoly Karpov came to Washington, DC for a tournament and gave a simultaneous exhibition. Clayton was on one of the boards and gained a hard-fought draw.

(See Karpov-Clayton) Clayton also won the 1960 Baltimore Open and was the subject of an interesting story reported on rec.games.chess by Steve Mayer:

Ken played an American GM in an international run by Bill Goichberg. Clayton played well, but ended up losing in a game that featured a key line in the GM’s repertoire. The bulletin editor offered a deal where anyone turning in a score would get a free copy of the bulletin; anyone else would have to pay 25 cents. The GM gave Clayton a quarter, and said, “This is for the bulletin. Please don’t submit the game.” And Clayton didn’t.

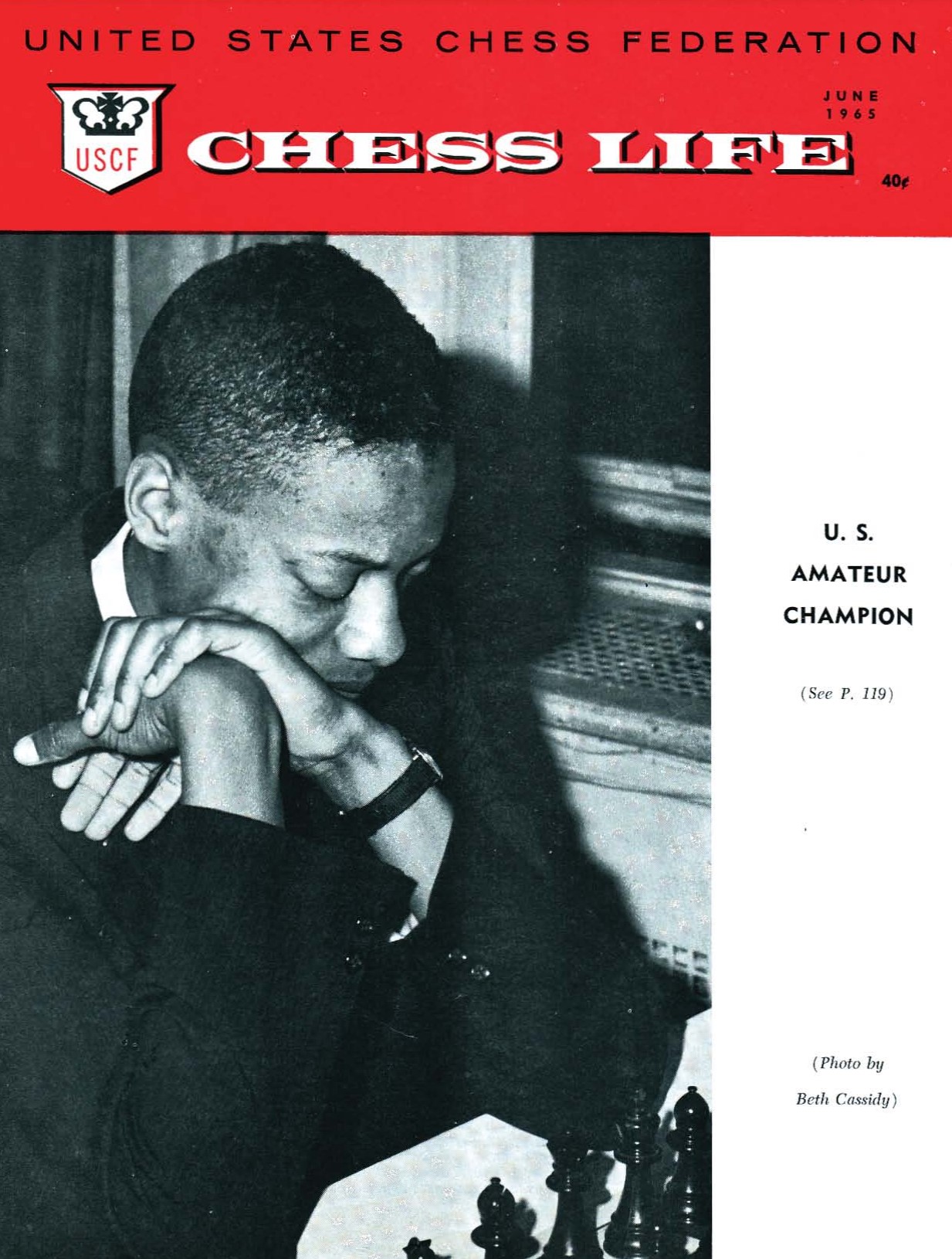

Frank Street, a Maryland resident, would be the 2nd Black player to earn the Master’s title in 1965 and in that year, won the prestigious U.S. Amateur Championship. He won the club championship at the premier chess club, the Washington Chess Divan, by defeating Clayton. He also competed in the elite Lone Pine tournaments in the 70s.

A graduate of both UCLA and University of Maryland, Street is currently an accomplished engineer in the space/satellite industry and resides in Bethesda, Maryland. He asserts, “Chess has been a great way to meet people and it has helped me to develop the confidence to go into many other intellectual areas.”

Covington was a different type of legend because he excelled in so many different areas. Noted as a talented musician, Covington found a zeal for chess a the ripe age of 25 and in between music gigs, he cut his teeth on many famous players on the east coast including Abraham Kupchik, Walter Browne and Asa Hoffman. In his memoirs, he described other encounters:

“The three biggest highlights in my chess career during the 70s were my draws against World Championship candidate, International Grandmaster Victor Korchnoy, Women’s World Champion Nona Gaprindashivili and of course, Grandmaster Bent Larsen. I was still on cloud nine from my 1972 exciting 66-move draw with International Grandmaster Bent Larsen and now I had the opportunity to play International Grandmaster Victor Korchnoy, or Victor the Terrible’ as he was known by.”

Covington has plans to make his chess contributions not necessarily by playing, but in his compilation of a compendium of chess history, anecdotes, games and problems. His book also features a stirring story about Baraka Shabazz, a teenage phenom of the early 80s. In his book, there is a picture of Baraka playing chess in Dupont Circle. This specimen of nearly 400 pages is commendable in its content as in its size and scope. Each player has a number of chess stories to tell, but only a handful of these thoughts are immortalized in a written format. Covington’s revised edition will be available in August 2005.

DC/Maryland: The Black Chess Mecca?

In America, most of the players from various cities, often meet at tournaments and talk with glee about the players their city has produced. Of course, New York has produced the likes of FM Alan Williams who preceded “Black Bears” GM Maurice Ashley, FM William Morrison (who has become a Maryland legend), FM Ronald Simpson, Ernest Colding and Jerald Times. Any history of New York area chess would be remiss if it did not include K.K. Karanja and Shearwood “Woody” McClelland, two players with outstanding scholastic credentials and the 2nd and 3rd youngest Black players to earn the title of U.S. National Master.

If we travel a bit south, we will find the rich history of Philadelphia and its famed history of Vaux Middle School and its own cadre of masters in FM Norman Rogers, Howard Daniels (youngest Black master ever), Wilbert Paige (now deceased), Elvin Wilson and Glenn Bady. However, Chicago also has its respective history led by strong masters FM Morris Giles, Marvin Dandridge with a large number of Candidate Masters. Travel to the west coast and you’ll find a contingent in Los Angeles. In days gone by, IM-elect Stephen Muhammad was the catalyst for fierce blitz tournaments in the LA area.

Saying this… is it safe to say that the DC/Maryland area remains as the Mecca of Black chess as it was in the 60s? New York could certainly hold such a claim, but this debate will never end as many players, such as Leroy (Jackson) Muhammad (4-time St. Louis Champion, 3-time Missouri State Champion & 1966 Eastern Open champion), Harris, Morrison and FM Emory Tate, are claimed by more than one city. Tate was actually born in Chicago, formative years spent in Indiana and his early successes were seen in these two places (and Air Force). Even Dupont Circle blitz legend Tom Murphy was raised in Philadelphia. In Kearse’s article, he raises the question, “What does it all mean?”

“On a practical level, there are enough black masters nationally spread out from California to upstate New York, who take a special interest and pride in bringing along other African-American players into the mainstream. These men are heroes in the black community and are role models in glittering contrast to the stark madness or urban designer drugs and random violence.

The larger mainstream society is beginning to recognize the importance of chess in the education and salvation of our nation’s youth. Chess clubs and programs are springing up around the country, and at the vanguard are the kids whom we have dubbed the lost generation all that black chess masters have been doing, almost from the very beginning, is passing on a legacy of excellence to the inheritors of the throne!“