Ending Laboratory (Rook)

Zambia’s FM Nase Lungu had a stellar tournament at the 9th All-Africa Games. He is a veteran who has represented his country in Olympiad tournaments for almost 20 years. In the position below, Lungu holds five menacing pawns against a lone rook. We are taught that five pawns equals a rook, but in the endings, pawns far outweigh the rook. Below we have a practical example from the 1990 Olympiad in Novi Sad (then Yugoslavia) between Lungu and Martin Marder-Riveda of Honduras.

After black’s 52…Kxe1, Lungu’s pawns steamrolled black’s rook without the aid of the king.

53.a5 Rb8 54.g5 Ke2 55.g6 Ke3 56.g7 Kf4 57.a6 Kg3 58.b7 Rd8 Hoping that Lungu would overlook a one-move mate. The Zambia replies beautifully with 59.g8Q+! 1-0 I found this game at OlimpBase.org which has games with interesting themes.

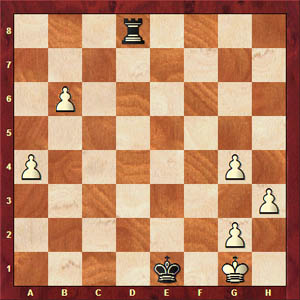

However, in the position below, we will make the contest a bit fairer. This is an interesting study from the Batsford Chess Ending encyclopedia. Despite the above example, the rook can often show off its amazing range and versatility against seemingly insurmountable odds. This ending is very practical and often times the rook finds itself having to chase down multiple pawns after a pawn race.

Obviously, White is on the defensive. Black is threatening 1…g3 after which it would be impossible to deal with all the pawns – or indeed 1…f3. So White’s move must be a choice between 1.Rf8 and 1.Rg8, but which one? Work it out!

White to move and draw!

OK… no one has bothered with this ending. I would hate to post only tactical puzzles, but it appears that chess players eschew endings because we rarely see them… or when we do, it isn’t one of those featured in books or magazines. The key here is to understand the principles and learn how to apply them.

I think it was FM Leonard Johnson whom I heard say he memorized 10 key Rook and Pawn endings and his rating increased rapidly. ❗ He probably saved and gained countless ½-points in this way. Endings also helps us to understand how to execute in the middlegame. It cuts down on calculation time and gives us a clear plan.

Nevertheless, here we go.

Diagram #1: White to play and draw. Should white play 1…Rf8 or 1…Rg8

1. Rg8! (1.Rf8?? f3 2.Rf4 b4 3.Rxg4 b3! 4.Rg1 b2 5.Rb1 f2 0-1 (See Diagram #2 below))

Diagram #2: White cannot prevent the king invasion.

1…g3 2. Rg4 b4 3. Rxf4 b3 4. Rf1 g2 5. Rg1 b2 Notice that the number of files between the pawns makes it impossible for the Black king to cover both sides of the board. This is why it was important to play 1.Rg8! to win the f-pawn instead of 1.Rf8?? to win the g-pawn.

So on (5… b2 6. Kg7 Kd4 7. Kf6 Ke3 8. Rb1! Kd3 9. Rg1 Ke3 10. Rb1 ½-½ (See Diagram #3 below)) ½-½ [Batsford Chess Endings]

Diagram #3: White can control both sides of board… draw!

One of the mistakes that we make in our studies and preparations is the neglect of endings. Maybe players don’t find endings attractive, but they can be very stunning. Of course, calculation has to be precise and the margin of error is so small which makes players dread them. It may take one awhile to appreciate endings, but it is only in the ending that one can appreciate the true power of the pieces. Maybe this is why they started with endings in the Soviet School of Chess. Hey… if we cannot handle a few pieces how will we keep track of 32!? 😕