Can you make a living playing chess?

A very interesting report has been released by World Chess, the marketing arm of FIDE. If one can get past the board that is set up wrong (black square on right), there are some very serious admissions in the report. However, one may wonder why FIDE is revealing such a sordid picture of the world of professional chess.

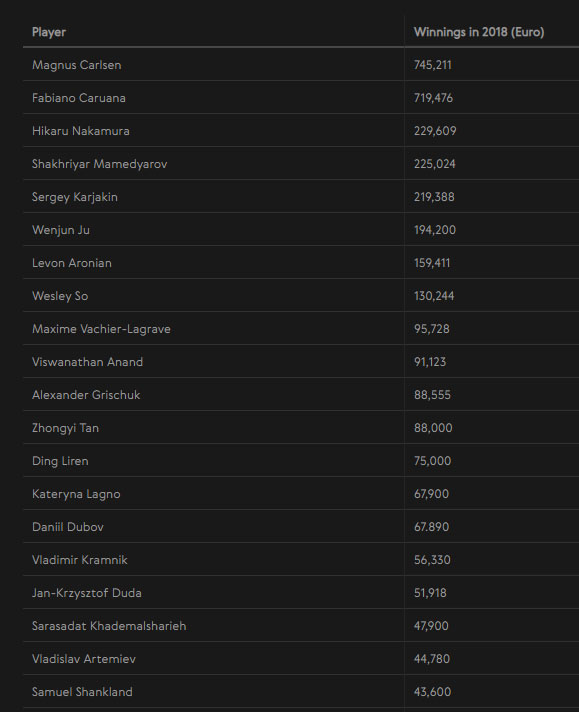

Certainly, one can be skeptical of the statistics, but there is no question that chess is essentially a competitive activity where only the top 10 players can earn a comfortable living. Note the top-heavy list at the end of the article. If that is the case, then what does the future bode for aspiring players who want to vie for the world championship? Should they set a title/rating/age cutoff before deciding to focus on a career where they can make a living?

“Chess can take you far, just not in chess.”

~GM Maurice Ashley

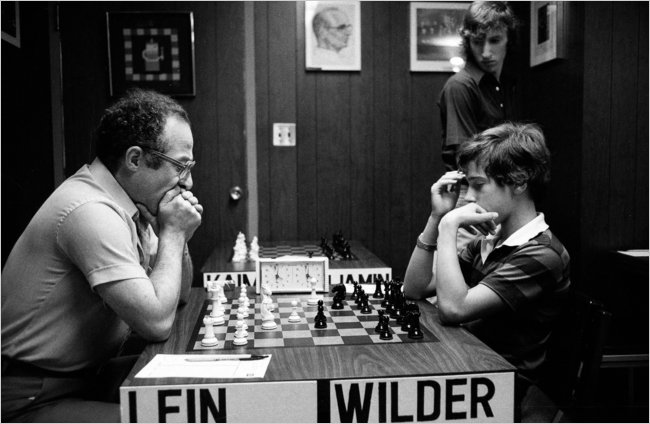

History is replete with examples of players who opted to leave professional chess after earning the Grandmaster title. In the U.S., Kenneth Rogoff, Michael Wilder, and Patrick Wolff were a few promising players who opted to leave chess for successful careers in the private sector. Rogoff is a top economist and policy consultant, while both Wilder and Wolff have been successful in law and finance, respectively.

Dylan Loeb McClain of the New York Times penned an interesting article, “Former Champions Find Success Beyond Chess,” interviewing Wilder, Wolff, and Alabama’s Stuart Rachels, once a teen phenom. These players were set to succeed other home-grown GMs such as Yasser Seirawan, Nick deFirmian, Larry Christiansen and John Fedorowicz.

Thirteen-year old Michael Wilder playing the Schleimann against Anatoly Lein

with Michael Rohde watching (1976).

Photo by Jack Manning (New York Times)

World Champion Magnus Carlsen tipped the money scales at €745,211 ($US839,800.63) followed by Fabiano Caruana at €719,476 ($US810,799.09). Most of these earnings are from their world championship match where they earned €600,000 and €400,000, respectively. Some of the figures on the prize rankings are truly shocking for players who spend an inordinate amount of time honing their craft.

Magnus Carlsen earned many times more than the €745,211 listed on the chart. Many of the top players have sponsorships and attract hefty appearance fees.

If we look at chess history, there are a number of players who eschewed chess for careers in science, medicine, law, finance, and academia. It is clear that chess provides the mental training to be successful in practically any field. Maurice Ashley said to me recently, “Chess can take you far, just not in chess.”

There is an understanding in the world of chess that there are many social benefits in playing. However, the most tangible benefit that I’ve seen in my 18 years of covering chess is providing an avenue for youth to develop skills, gain confidence, and to gain admission into their school of choice. In addition to getting exposure from winning trophies, chess is a trump card on college and job applications where it commands respect.

In fact, a recent article written by Mike Klein on chess.com cited research that showed chess provides tangible benefits in the lower grades when critical thinking skills are developing at a high rate. As far as embarking on a career in chess, it remains a choice with tremendous opportunity costs. After being inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in April 2016, Ashley gave a number of interviews. One was highlighted in Yahoo! Finance in which he stated,

“The reality for a person like me is if you never make it to the top 20 in the world, there are very limited ways to make money in chess,” he tells Yahoo Finance. “Teaching is the most consistent, because people want to get coached by a grandmaster. That’s nice money. Writing books, doing lectures, doing appearances. I do live commentary online for tournaments around the world. So a grandmaster has to cobble together all that stuff. Otherwise you’ll starve. You can’t make a living if you only play.”

After earning the GM title in 1999, Maurice Ashley was on the professional circuit for several years, winning 2000 & 2001 Foxwoods Open. In his highest-earning year, he found that such a lifestyle would not be economically sustainable when accounting for many factors. He found other ways to earn a living in chess and is now a world-class commentator. Photo courtesy of Maurice Ashley.

There is this burning question about chess when talking about how to harness talent. How does one justify spending an inordinate amount of time studying chess when the financial payoff is so little? I personally have known a number of players who have invested decades in focusing on chess with little material sustenance. It’s a serious question for any young player to consider and perhaps looking up the term “opportunity cost” would help.

As we look at some of these figures, we can only think about whether there is a future for the million-dollar tournaments that Ashley organized. There was a lot of debate during that period. The million-dollar model was not sustainable for a number of reasons, but the new FIDE President Arkady Dvorkovich will have his work cut out so that many talented players will have a chance to earn a decent living if they choose to be a championship contender.

Link to full list: https://worldchess.com/news/898

Many of the top players on the list were part of the Grand Chess Tour. Imagine how this list would look without this series of tournaments. Practically the same players compete in all the tournaments.

as usual…good educative read

There is intense, irrational resistance among chess players and administrators alike to innovation. The miserable compensation levels here are heavily self-inflicted and are mostly deserved. Millionaire Chess faced bizarre resistance from the people who most stood to benefit from it. I cannot think of any other game or sport of any popularity remotely approaching chess with such incompetent professionals and administrators. I myself have invented a reform effort consisting of tournaments spread over multiple physical sites. The USCF promised to rate my tournaments, then reneged with no reason given. They are rating the scandal-plagued ChessKid online-only tournaments, but not mine.

The lopsided distribution of income of the top 100 places is likened to an impoverished nation where only a small percentage of inhabitants control most of the wealth. It had been the same in looking at the balance of power in chess… only a handful of the nations would be contenders for top medals. The balance of power is changing in terms of federations, but not in terms of professional chess. The same players stand to benefit from the expansion of the Grand Chess Tour. This is great, but there needs to be more opportunities for those outside the top 10 or we will see many more Michael Wilders. We get back to the question of sponsorship. When will chess find a formula to make a breakthrough?

The figures from FIDE is completely off and has been debunked by a number of players themselves. In addition, some events pay 5-10-20 times more in appearance fees than actual prizes. Chess income structure is different than many other sports.

Yes… I have made mention of the other residual income such as appearance fees, sponsorship and Internet winnings. Even if the numbers are off, I believe there is still a very salient question about whether playing chess is a sustainable profession. We all know that in most countries, it is not.

In the U.S., it is difficult to be a professional chess player unless you have a sponsor, or a residual income. It seems that scholastic players (whose parents are sponsors) can put in that time and energy. If you are an adult with responsibilities, the expense of travel combined with the lack of professional conditions are a deterrent.

In U.S. tournaments, there is usually an exemption of an entry fee. Some players can command conditions, but a rare few. I know a number of players who were chess professionals. Some of them were in dire straits before deciding to find another way to make a living. We are not even speaking about top 100 in the world, but top 100 in the country.

I think we need to be brutally honest about professional chess. It’s still top-heavy and if not for the relatively new Grand Chess Tour, professionals would be resigned to finding other ways to supplement income to take care of families and personal affairs.

I believe Kasparov might make this list, but am not sure Magnus would yet, though he might in time: https://moneyinc.com/richest-poker-players-in-the-world/

I don’t think any other players are even close. I see no signs at all that chess administration will open up to bigger revenues. The higher echelons are very much based on a philanthropic sponsorship model which is very cramping for earnings relative to even far less popular sports and games.

Thanks Jones! Good contrast.

One huge difference is the age demographic. Poker has a much older audience that allows gambling high-stakes. I believe we can find a model, but it probably will not approach the lucrative pots of poker until we find a way to package it on TV. Chess has an age old image that it is hard to understand. We have to somehow rebrand chess.

Chess had it’s moment on the sun when it was fashionable and trendy – during the Fischer boom. The $5 million purse for the 1975 Fischer – Karpov match was stratospheric back then. No other sport had prizes that came close, outside of Muhammad Ali title fights (and Fischer wanted pay equity with Ali!)

The LOSER’S share (1/3) of that 1975 purse would have been more than the highest paid baseball player (Hank Aaron, under $300K per year), the highest paid tennis player (Arthur Ashe won Wimbledon in 1975, and a cash prize of 10,000 pounds), the highest paid golf player, the highest paid NBA player, the highest paid NFL player, the highest paid soccer player, and the highest paid NHL player made in 1975 salary/prizes COMBINED.

And we all know that will never happen again

That moment was squandered because the Soviets and their cronies in FIDE (including President Euwe) decided to play petty politics instead. Rejecting a ‘champion retains title on a tie’ clause that every other World Champion received automatically… the predictable result being, Fischer walking away (he was quoted in his biography ‘Endgame’ as saying “I will punish them by NOT playing!”)….the Soviet regaining ‘their’ title the only way they could, off the board…and chess returning to the days of anonymity, back rooms and penny prize funds where it remains to this day

Miro,

Great points.

I’m wondering when we will ever find the formula. We may not get Fischer Boom again, but perhaps we’ll have something we can build on. The current Swiss tournaments that are funded by class players is a dead model. There needs to be serious sponsorship in chess if we want to see greater professionalism.

The Fischer boom did prove there can be a wide audience for chess though, given the right circumstances.

We’ll never see the events that characterized the Fischer boom again (the Cold War drama, also it was the pre-internet days when there was less competition for viewers’ attention). But we can see a situation again where a lot of people will pay attention to chess.

My first suggestion is bring back the 3-1-0 football scoring. When it was used, it massively increased the number of decisive games in elite tournaments and virtually eliminated the GM draw. But for some reason it was abandoned…. and I think this is due to the “intense, irrational resistance among chess players and administrators alike to innovation” Jones Murphy mentioned.

Chess can be an exciting and captivating game, even to those who barely play. In 1972 non-players and rank beginners were glued to the Shelby Lyman telecast for hours, watching move by move.

That’s because Fischer and Spassky also played good, real, fighting chess games. There was not a single GM draw in that match, because Fischer played every game for a win (he also did not offer a draw once in that match). The 3-1-0 scoring forces everyone to play like Fischer – until there is literally no play left in the position

I remember the 3-1-0 format. I think Linares was using that before the tournament folded.

I believe we are close to finding the combination and the internet platform seems to be made for chess. We can use that platform in a creative way, but we haven’t figured it out yet. The commentary is great, but how to you sell it to sponsors. That is the elusive answer.

I remember when Maurice wrote the “End of the Draw Offer” essay and it was a big deal. It has helped, but the issue is still plaguing chess. I don’t think it is because there is perfection, but that the same set of players are always competing so the familiarity breeds some sense of caution.

Fischer was a different breed and did it alone. He was one of the greatest raw talents we’ve seen. He showed us how chess should be played… with a vibrant spirit.

Interesting interview of Hikaru Nakamura by Mark Rubery…

Here’s one excerpt that sticks out:

Mark Rubery Chess (Cape Argus, 22 February 2019)

The American GM, Hikaru Nakamura, gave an interview to John Cox on Chess. com last month and fielded a few questions that highlighted his pragmatic approach to chess as a profession.

Q: By 17, you were a GM and the youngest U.S. chess champion since Bobby Fischer, but you ended up quitting the game altogether for six months. What happened?

I think I realized I wasn’t good enough. I’d hit a wall and plateaued around the top 100 in the world. One of the most brutal parts of chess is that there are so many people who are incredibly strong. There are some GMs, who I knew while growing up, and I thought they were so much more talented than me, but they never quite made it. Unless you’re in the top 20 and getting invitations to events with the bigger prize funds, there’s no guarantee of making a stable living. If you’re not, you’re playing these big opens, where first prize is no more than $10,000, and you’re not going to win them all. So I wasn’t making a great living at all, and I’d been traveling constantly for about seven years. I was just burned out.

Q: How did you find college and what drew you back to chess?

The thing I disliked most about college was it felt like there was a class system. Growing up in the chess world, your age, background, ethnicity—none of these things mattered. It was just about how good you were. For me, the fact that being older in college, meant you were viewed as more important. I strongly disliked that. It made me realize how in many ways, chess is better than the real world. So over Thanksgiving, I decided to go and play this tournament in Philadelphia. I hadn’t looked at chess for six months, but I actually won the event. I scored 5.5/6 against GMs, and that kind of reignited the passion. It really motivated me. I wanted to start playing more again.

Q: You’re quite unusual for an elite chess player, in that you have such a range of interests. What led to that?

I love chess, but if you’re just obsessed with that one thing, eventually you will go a little bit insane. For me, hiking or following the markets clears my mind. You really need that as a player, because there are going to be very bad periods where you don’t do well. If you don’t have any outlets, you kind of lose it when you have bad events, and it’s very easy to get angry and be like, “I’m going to quit tomorrow. Enough is enough.” And one of the things I’ve noticed with chess players generally, like Yasser Seirawan for instance, they’re still tied to the game after their money-making days are gone. So they have to teach, commentate, do everything to still try and get an income. I’ve always been interested in investing to have some form of financial independence when I stop playing, so I can go and do something completely different.

If someone win the chess competition and the person is underage, does they give the money for that person parent?????

I’m not 100% certain, I would imagine they will put the winner’s name on the check. Generally, the parent would have to cash or deposit the winnings for the child if they don’t have a bank account.

Hikaru Nakamura: Meet the world’s wealthiest chess player

https://english.elpais.com/economy-and-business/2022-06-29/hikaru-nakamura-meet-the-worlds-wealthiest-chess-player.html