Why are numbers declining in Black Chess?

There seems to be a decline in the number of Black players participating in major U.S. tournaments. The World Open is one of America’s marquee events and is typically a chess tournament where many players want to make magic happen. It is also the tournament that acts as a sort of barometer for where American chess is headed. It was once a must-attend event for those seeking norms when there were few other opportunities. For the players of the African Diaspora, it was typically a place where you could find the strongest collection of players in the Western Hemisphere.

Drum Majors at 2009 World Open (L-R): NM Dr. Okechukwu Iwu, IM Oladapo Adu, FM Farai Mandizha, IM Emory Tate, FM William Morrison, NM Norman Rogers.

IM Emory Tate, IM Stephen Muhammad, IM Farai Mandizha, FM William Morrison, and FM Norman Rogers all picked up norms at World Open tournaments. Other players like and IM Oladapo Adu has made many appearances. Brewington Hardaway and Tani Adewumi are part of the new generation battling for GM norms. However, in the World Open earlier this month, many faces were missing in the African Diaspora.

This author discussed this with Adia Onyango, and she noted immediately that there were Black players “missing in action.” Out of 1200 players, just under 3% representing the African Diaspora participated. This is a relatively low number and below the numbers usually seen across the board. Mario Marshall, who visited the tournament, also noticed a diminished presence and less excitement from previous years.

What could be the reasons?

In what follows, I will list factors that could possibly explain the decline. These reasons are based on anecdotal evidence, so they may not reflect the accuracy needed to draw definitive conclusions. The U.S. Chess only collects age and gender data, so ethnic data are incomplete. Despite this missing data, we were able to give approximations.

Five factors that may contribute to the current decline in Black participation are:

- Post-COVID Drift

- Rising Costs

- Changing Atmosphere

- Blitz Training vs. “Fast Food Chess”

- Attrition

Post-COVID Drift

It is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic opened up new possibilities for chess and provided players with a platform when over-the-board (OTB) tournaments were at a standstill. During the OTB ban, many took memberships on one of the popular servers and moved to organize their own online events. A large majority of them emphasized cage matches featuring blitz and bullet chess. It was something people got used to very quickly, and the popularity of these events grew.

Many claimed that quickplay would overtake classical chess as the preferable playing discipline. While more options have emerged for online play, classical tournaments are still the gold standard as far as chess prestige is concerned. Incidentally, FIDE titles, norms, and the path to world titles are only earned through OTB play. In addition, cheating scandals have largely delegitimized online play as a credible substitute for OTB play.

FM Jimmy Canty has turned his Twitch streaming success into a career that has taken him around the world commentating on top-level events. He has also produced Chessable courses. Photo by Nathan Kelly.

Many of those online activities ran their course quickly due to little differentiation. Bear in mind that online blitz has been available for decades, so the market was already crowded. One way players established their unique brands was live streaming via Twitch. Some even signed on with sponsors, officially embarking on careers as social media influencers.

Online chess became a potentially profitable industry. There were a few popular streamers in the African Diaspora, such as IM Kassa Korley, FM James Canty III, and Frank Johnson. When OTB resumed, there seemed to be a “drift” from OTB tournament activity to lichess.org/chess.com, which seemed to provide more value.

In recent years, the cost of air travel has skyrocketed and is now $200-$300 more than in pre-COVID times.

Philadelphia is the host of the World Open, a place of history and intrigue.

Photos by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Rising Costs

It is possible that the rising cost of travel makes the expenses more than many can bear. Given that tournament prize funds are not increasing in proportion to the cost of living, it is becoming a less attractive financial proposition. Then there is the notion of competing against fully funded, fully motivated, scholastic players hungry for norms, titles, and rating points. They play without financial pressures and fear no one. That is the reality of American chess.

As for the World Open, it remains the marquee tournament in the U.S. It used to serve as a type of reunion but also a way to test one’s skills against the world’s best. However, in recent years, the cost of air travel has skyrocketed and is now $200-$300 more than in pre-COVID times. If you are not in a drivable distance to Philadelphia’s World Open, you are going to spend $1500-$2000 in expenses for five days unless you get a couple of roommates to split the costs.

Changing Atmosphere

Those of us old enough will remember the World Open at the Adams Mark Hotel. There was a certain magic about the place. The “skittles” room had something for everyone: someone selling snacks, someone selling t-shirts, and backgammon games going on. The blitz battles and serious post-mortem sessions kept the place buzzing until security came to lock the room.

The language was colorful and not necessarily kid-friendly. Some of the chess hustlers would even go elsewhere and battle through the night! Emory Tate always came to the World Open seeking center stage in the skittles room. His dramatic post-mortem performances were a big attraction, and he always made an impression.

IM Emory Tate in one of his classic post-mortem sessions. He received raucous applause after finishing the session with a flourish. Many of the Black masters from his era have either retired, played infrequently, or passed on. Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

The face of American chess tournaments has totally changed in the past twenty years. They have changed from an adult-orientated activity to one dominated by minors. While this is not a problem in general, it does make for awkward interactions at times in the common spaces. Even interactions at the board are sometimes an issue when young players may not be as mindful of chess etiquette. These are things you hear in random conversations among adult players.

Scholastic players are a lot more confident than in previous generations. Many have professional trainers, a collaborative spirit, and generally are better prepared. It is also a confidence booster that they see half of the tournament entries consist of their peers. In previous generations, tournament players were much older and more experienced, with only a handful of high school students playing in open tournaments. Today, young players have access to more resources and are relatively stronger. It is a sobering reality when the adult player repeatedly loses to players who are essentially schoolchildren.

Blitz Training vs. “Fast Food Chess”

Blitz chess has a special place in the Black community because it is the one arena where everyone has an opportunity to establish an identity quickly. The only cost is time and one’s ego. Despite the brutal nature of losses, social interactions are fulfilling and serve as a bonding experience. Sometimes, these groups are formalized, and blitz matches are held as a training ground for improvement. That is exactly one of the features of the “Black Bear School of Chess.”

The “Black Bear School” used 30-game blitz matches as an integral part of training.

Photo by Jerry Bibuld

Blitz can definitely be a valuable training tool. I remember playing a Texas master Dee Drake in a series of blitz games where we studied the Sicilian Dragon. We played the opening in blitz, analyzed the games quickly, switched colors, and then continued. It was one of the most useful sessions I ever experienced. Unlike the blitz training employed by some players to test opening ideas, it has been my contention that blitz in the Black community has become a substitute for any serious training.

It is common to see players playing blitz for money in between rounds of a serious tournament. Where is the focus? Blitz is indeed an enjoyable activity, but endless play becomes what I call “fast food chess.” The problem with consuming fast food is that you satisfy your hunger quickly, but your intake may not provide you with long-term, nutritional sustenance. You play a game, lose/win, and set up the pieces to start a new game. Blitz can be a wonderful training tool, but too much of it ruins your long-term attention for classical chess.

Attrition

It goes without saying that the golden period for Black chess occurred in the 80s when most of the masters emerged. It was a period on the tail-end of the “Fischer Boom” that created pockets of activity in many of the urban centers around the country. Jerry Bibuld, who compiled his list of “Afro-American Masters,” documented players and their first known master rating.

On a list dated March 5th, 1989, four Black players earned their National Master title in the 60s, three in the 70s, and 37 earned the title in the 80s. After further research, the number was closer to 50 Black masters produced in the 80s. This was quite an accomplishment in days when earning a 2200 rating was no small feat.

One of the most ferocious African-American players you may not know. FM Morris Giles was a “Fischer Clone,” playing all of Fischer’s openings, including the King’s Gambit. The Chicago native played in a brutal style and is famous for mating GM Walter Browne in the middle of the board with a queen sacrifice. He was one of the most active players in the 80s until one day, he lost interest in chess.

Since the 1980s, there has not been much development to keep Black talent flowing. There are many initiatives to expose Black children to chess, but there is little to keep them engaged. Many do not have a sense of history and lessons to draw from. Certainly, The Chess Drum has recorded history, but it is not being emphasized. One coach that does emphasize historical legacy is National Master Glenn Bady, who recently earned his certificate as FIDE trainer. Sometimes a sense of history is important to take young players to the next level.

In subsequent decades, a spattering of Black masters have emerged, including several titled players. Despite having more opportunities for norms than in previous decades, those seeking higher titles seem to struggle in executing plans. When chatting with some of these players about charting a path and finding them resources or a trainer, they often give the impression that they want to do things on their own. Getting a FIDE title without a trainer is like trying to learn an advanced subject by reading books on your own. It’s very inefficient, and it lacks practical application.

The World Open has always been a stage for rising talent. Fabiano Caruana playing Dr. Kimani Stancil. Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

2024 World Open in Perspective

There was once a time when seasoned veterans came to the World Open with ambitions of large winnings. Those times seemed to have passed as most elite players no longer partake in the summer classic. This year, 21-year-old Grandmaster Awonder Liang won clear first and represented a breakthrough for the Wisconsin native. The World Open is a tournament stage where one can have a career result and get on a path to more tournament invitations. Hans Niemann won the 2021 World Open and started a similar rise to stardom.

Last year, The Chess Drum ran a lengthy article on the World Open tournament. It details the evolution of the tournament, from when it attracted the world’s elite players until the current time when top players have avoided the tournament. This has been due to the proliferation of underrated players feasting for norms, titles, and Elo points. This year, one can see the fruits of America’s scholastic boom as teen Grandmasters Christopher Yoo, Arthur Guo, and Andrew Hong were competing near the top boards for the entire tournament. GMs John Burke and Andrew Hong were also in the mix. This is a favorable trend, and as mentioned, younger players are stronger than before.

Other trends show a disturbing pattern.

African Diaspora at World Open

For the past few years, there has been discussion on tapping the market of chess players from underrepresented communities. As part of this initiative, U.S. Chess has created a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) committee. How does U.S. Chess attract more enthusiasts to tournament chess and retain them? We’ve discussed the role of analytics in target marketing on these pages. One of the critical questions is also reaching the Black community of chess players. Typically, there is a stable percentage of Black players at major events, but at the 2024 World Open, the word was that there were lower numbers.

In this year’s event, I looked at the charts and noticed a decline in the overall participation of Black players. There were 11 in the open section, including three internationals. IM Brewington Hardaway (6/9), FM Tani Adewumi (4/7) are talented juniors with title ambitions. Tani just won the U.S. Cadet a week before the World Open. Unfortunately, he withdrew from the tournament on a controversy. Trinidadians FM Ryan Harper (5.5/9), FM Joshua Johnson (5/9), and Jamaica’s Duane Rowe (2.5/6) kept up the tradition of Caribbean participation.

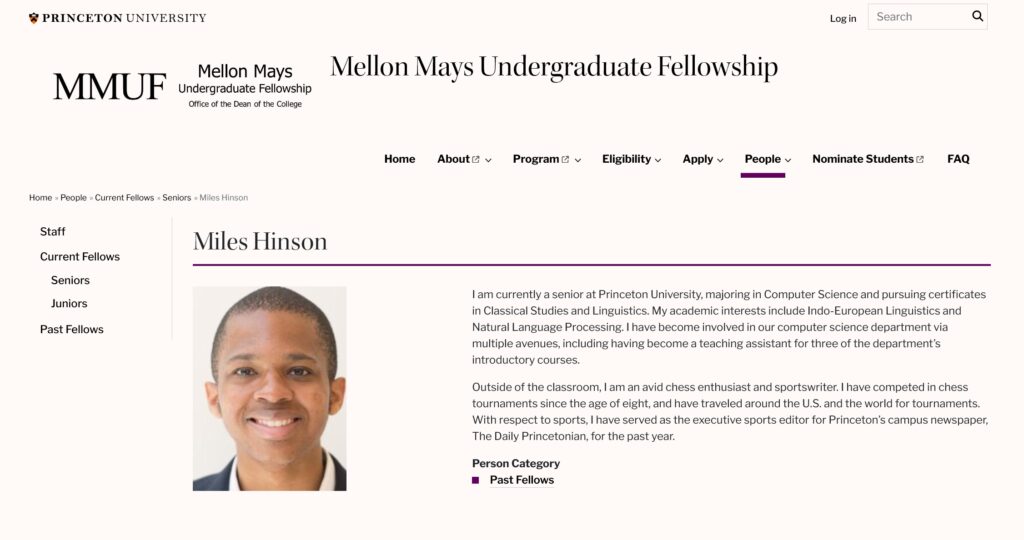

Others in the Open Section were: Dr. Kimani Stancil (2.5/9), Princeton’s Miles Hinson (2.5/9), Antoine Hutchinson (2.5/8), David Paulina (2/7), FM Norman Rogers (1.5/7) and Ernest Colding (1/5). As noted, most did not finish all nine rounds of the tournament for a variety of reasons.

Princeton’s Miles Hinson reminds me of NMs William Lopes (U. of Chicago) and Tyrone Davis III (MIT). Look them up!

In the under-2200, Jessica Hyatt was joined by Lamel McBryde, Rafael Calderon, Calvin Marshall, Mulazim Muwwakkil, and England’s Paul Obiamiwe. In the under-2000, Adia Onyango, Peter Pritchett, Justin Dalhouse, Wilbert Brown, James Jeffery, and Rico Adkins. Other names this reading audience may recognize are Vanita Young, Guy Colas, and Noni Hardaway. Lastly, Jeremiah Williams, Peter Moss, and Eric Kennedy played in side events.

Final Thoughts

In my 23 years of covering chess in the African Diaspora, I have enjoyed posting stories of unheralded figures. The mission is to show the universal appeal of chess and provide a Pan-African spotlight where it would not normally exist. Since Maurice Ashley earned the Grandmaster title in 1999, there has yet to be another African-American which is alarming. Brewington Hardaway is poised to be the next. There have been several stories here about IM Kassa Korley, IM Justus Williams and FM Joshua Colas earning GM norms. While they have all competed this year, the GM goal remains elusive.

In the past five years, there have been fewer stories about general chess news among African-Americans. Hardaway and Adewumi have been the subject of most of the news. However, we have to celebrate what we have. The most recent story has been Miami’s Shama Yisrael earning the title of National Master and writing a new chapter for chess excellence in the African Diaspora. Prior to that, 14-year-old Jacory Bynum, also of Florida, earned his National Master’s title.

Both Shama Yisrael and Jacory Bynum recently earned the title of National Master!

If we want to see more of these success stories, we have to have greater collaboraion. In the 80s, there were tremendous rivalries built, but there was also positive peer pressure. One’s success would motivate the next player and there was a sense of community. Today, there is very little collaboration happening in the African-American community. Let’s not invest our energy, time and resources primarily into blitz events. It is high time, that we spend more time organizing events that will put players in the best position to succeed in chess and make their marks in the history of chess.