Walter Harris, America’s 1st Black Chess Master, dead at 83

Yesterday, I learned that Walter Harris, America’s first Black National Master, had passed away on October 12th, 2024. Harris was 83 at the time of his demise and had no survivors. During a phone conversation with Frank Street (America’s second Black National Master), he expressed a concern that he had not heard from Harris in a few months despite previous regular communication.

After a quick Google search, I came across a notice from the Northern Virginia Burial & Cremation Society for “Walter Harris.” There was no obituary, but I verified his identity by the birthdate, which he gave me personally. Harris was born at Seaview Hospital in New York, September 28, 1941 to Walter and Mary Johnson Harris. There are few public family records. According to New York, U.S., Episcopal Diocese of New York Church Records, he was baptized at age three on October 10th, 1944 at City Mission Society. Unfortunate circumstances resulted in young Harris spending part of his childhood in a Bronx orphanage, but this would not prevent him from attaining tremendous success in physics and in chess.

After a quick Google search, I came across a notice from the Northern Virginia Burial & Cremation Society for “Walter Harris.” There was no obituary, but I verified his identity by the birthdate, which he gave me personally. Harris was born at Seaview Hospital in New York, September 28, 1941 to Walter and Mary Johnson Harris. There are few public family records. According to New York, U.S., Episcopal Diocese of New York Church Records, he was baptized at age three on October 10th, 1944 at City Mission Society. Unfortunate circumstances resulted in young Harris spending part of his childhood in a Bronx orphanage, but this would not prevent him from attaining tremendous success in physics and in chess. After serving in the Air Force, he studied physics at UCLA and the University of California-Berkeley followed by a distinguished career at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory. Upon retirement, he moved to Arlington, Virginia, but worked at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, DC. He lived in Arlington until his passing.

Below is a tribute to this trailblazer. May our memory of him remain strong.

Daaim Shabazz, The Chess Drum

WALTER HARRIS

(September 28th, 1941 – October 12th, 2024)

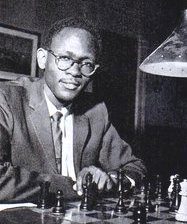

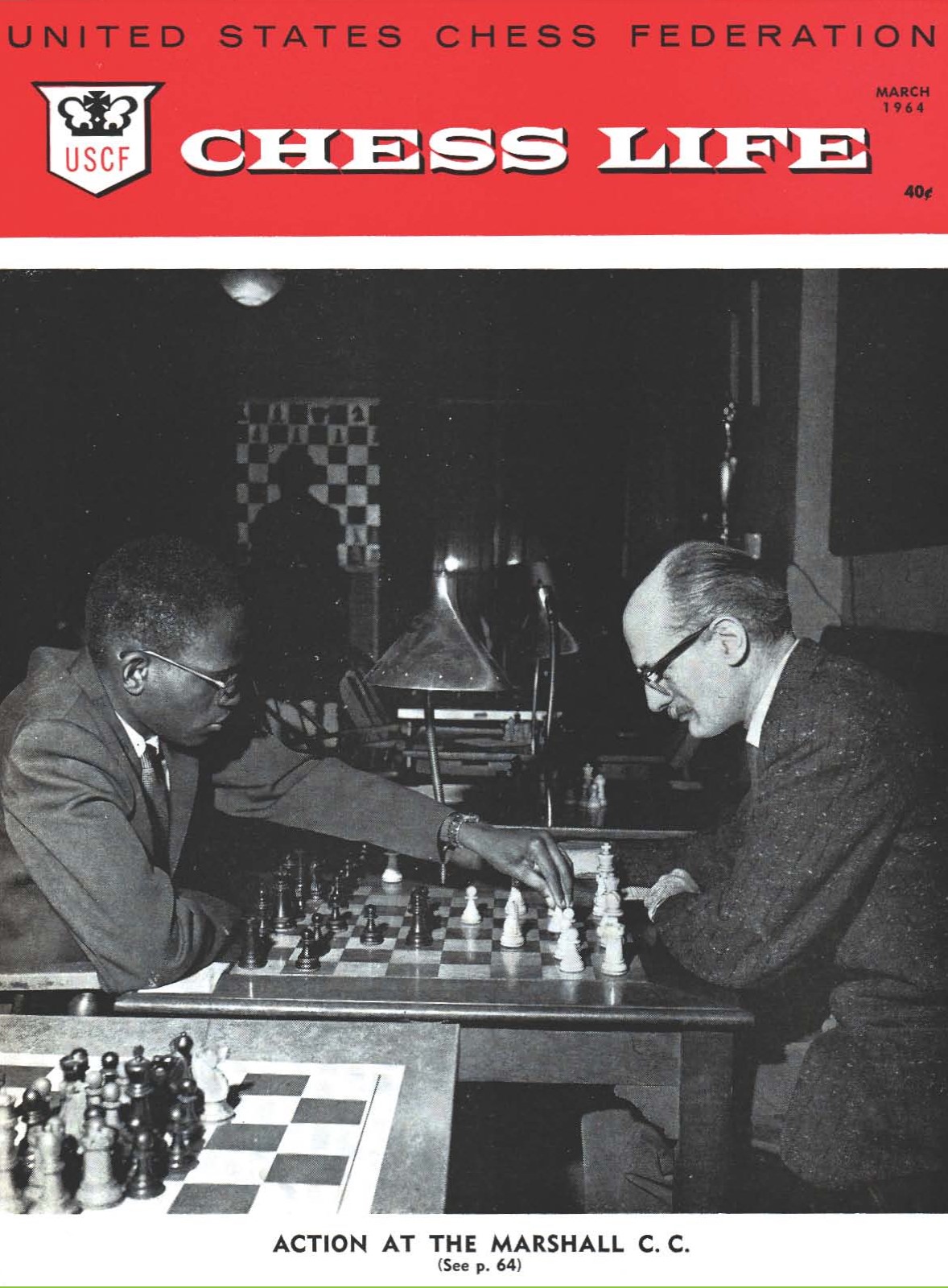

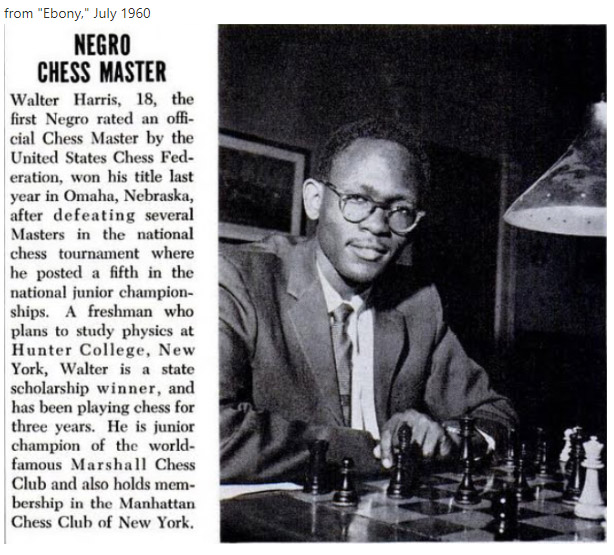

The story of Walter Harris is a testament to how one can still succeed despite unfortunate beginnings. Harris had been known as the “first Negro Chess Master” but told The Chess Drum in an interview that he was not seeking to make history. Earning the National Master during such a time when there was racial exclusion was quite a feat. It is unclear when he earned the title, but Ebony magazine ran a short article with his photo announcing the feat. In an e-mail, I informed him that Kenneth Clayton (America’s fourth Black National Master) had passed away but I also asked him the time he earned the title.

From: Walter Harris

Sent: Saturday, December 30, 2017 4:23 PM

To: ‘The Chess Drum’ <webmaster@thechessdrum.net>

Subject: RE: Kenneth Clayton and a questionDaaim,

I am so sorry to hear that Kenneth Clayton passed away a few days ago. While Kenneth and I have not been in touch for a while I remember him as a strong player who was easy to engage.

On occasion, people ask me that question. Over the last 50 plus years, since I became a master, I have not given a lot of thought to exact times and dates. However, I do remember that I earned the title at the US Open, in St. Louis, Missouri around July/August 1960. The title was not actually awarded until the following year, when the new ratings came out.

Walter Harris

The Young Master

Harris’ 5th place finish in the 1959 U.S. Junior set the stage for earning the National Master title the following year. He also played in the 1959 U.S. Open that same week, starting 7/9, including a first-round win over 1958 Junior Champion Raymond Weinstein.

Facing stiffer competition in later rounds, he lost his last three games, including games to International Master James Sherwin, computer chess trailblazer Dr. Hans Berliner and in the final round to Cuban master Eleazar Jiminez Zerquera. Berliner pioneered one of the first chess supercomputers in HITECH while a professor at Carnegie-Mellon University.

In their game, Harris had refused Berliner’s draw offer and went on to lose. He found humor in the setback by joking, “Adventurous hearts are ten times bigger, but my head was ten times bigger.” Harris would have been a bit better on 23…Reb8!

1959 U.S. Open Cross Table

(Walter Harris scored 7/12)

There was another side story involving Berliner, who was a well-respected International Master. Harris recalled beating Arnold Denker, who was upset at losing the game. In the postmortem, Denker kept trying to prove that he was winning at every turn and called Berliner over to confirm. Harris sensed a bit of arrogance from the famous American icon. Unfortunately, Harris didn’t have his old acquaintance Bobby Fischer to back his points.

Rubbing Shoulders with Fischer

Chess in America was still finding its footing as there were very few tournaments, and it was hard to make an impact. While Harris was a budding talent, he was taken under the win of Archie Waters, a journalist and mentor of Bobby Fischer. Waters can be seen in Fischer’s entourage in Reykjavik, Iceland, and was touted as his “ping-pong” sparring partner. In reality, Waters mentored Fischer as a teen and financed Harris’s membership in the Marshall and Manhattan Chess Clubs. He was also a frequent visitor of the Hawthorne Chess Club, but it was in the Manhattan Chess Club that Waters introduced Harris to Fischer.

Harris described the encounter:

I still remember it. It was almost like yesterday when I walked into the Manhattan Chess Club, and there were a group of players over in one corner. Fischer was one of those players. I didn’t know who he was and how accomplished he was at the time.

After being introduced and seeing Harris’ strength, Fischer seemed impressed. Harris later asked him questions about his chances of becoming a Senior Master. Fischer affirmed to him that he was a promising player, and he didn’t see why he couldn’t make it. Harris mentioned they had further conversations about chess and played blitz games. He had two minutes, and Fischer took thirty seconds!

At the time they met, Fischer was 14 and already in a league of his own. Harris had fond memories of Fischer. He also mentioned William Lombardy, the Byrne brothers (Robert and Donald), and Arnold Denker as people with whom he interacted.

Following is a game from Bobby Fischer’s 1958 simultaneous in New York:

I will always remember him as the great player that he was and what he gave to the game. I too will not dwell on the sadder aspects of his life.

~Harris on Bobby Fischer

Conversations with Walter Harris

I first heard about Harris from Jerry Bibuld, who photographed and documented the activities of Black chess masters worldwide for many years. I also learned from Philadelphia master Wilbert Paige that Harris appeared in an encyclopedia. I planned to research documentation on these legends, which led to the founding of The Chess Drum.

During the 2005 World Open, National Master Charles Covington, gave me a sliver of paper with Harris’s phone number. The number stayed on my desk for months. I finally called him for the first time on December 24th, 2005, exactly 19 years ago. I asked for Walter Harris, and in a relatively soft yet dignified voice, he said, “It is he.”

He shared involving the reality of racism at the time. Here is an excerpt from an article I wrote after our conversation.

During our conversation about the 1959 U.S. Open, Harris mentioned a story about not being able to rent a room at a hotel because he was Black. He could not remember if this incident occurred at the same hotel where the tournament was being held (Sheraton- Fontenelle Hotel). In those days, segregation ruled the day and Blacks were not allowed access to public facilities. The managers had pulled Anthony Saidy (now an IM) aside and told him that Harris was not welcome. Saidy protested, but the hotel managers were adamant. They went to another hotel where they were able to find accommodations.

Daaim Shabazz, “A Conversation with Walter Harris,” The Chess Drum, 7 January 2006.

Harris said he had heard of The Chess Drum from Covington and was astonished that he was considered a legendary figure. He had not been active but recalled hearing his name on a TV program about his chess accomplishments. He said he was lying down when the presenter mentioned “Walter Harris” as the first Black chess master!

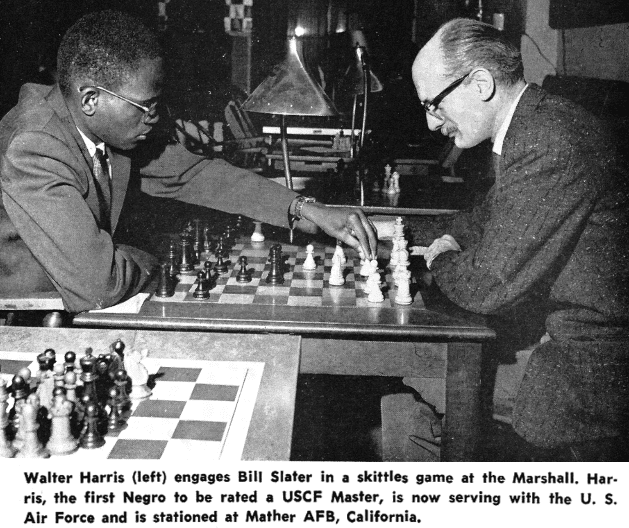

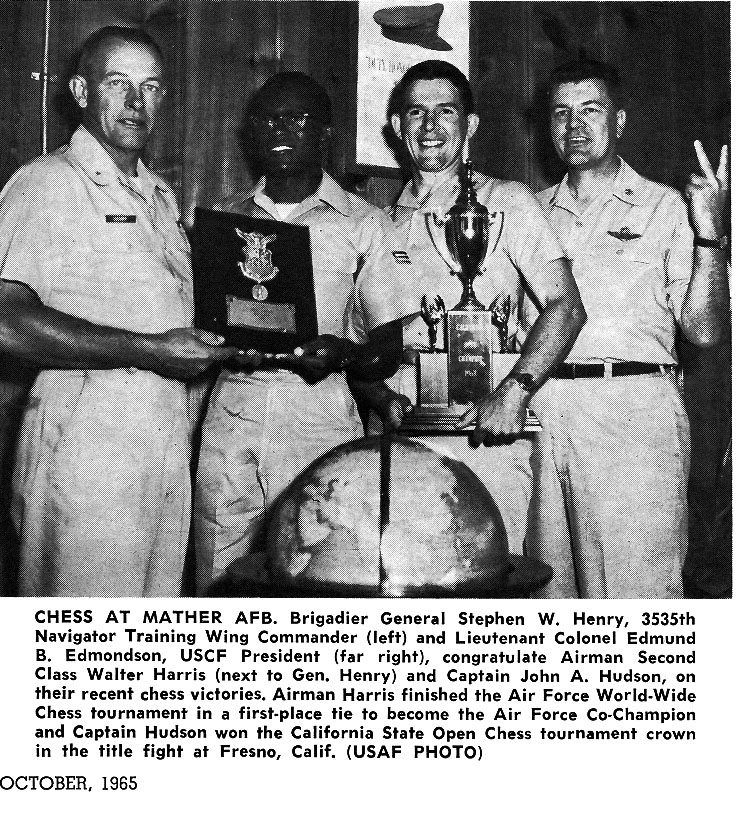

Harris did not speak much about his service in the U.S. Air Force, but he competed in the Armed Forces Championships during his four years of enlistment. He tied for first with Ross Sprague in the 1965 Air Force Championship. He served at Mathers AFB near Sacramento and won the city championship in 1964 and 1967. Interestingly, Bobby Fischer had come to the 1964 tournament to give a simul in Sacramento.

The first photo I saw of Harris was taken during the 1966 Armed Forces tournament, where Harris was watching the finalists. It was featured in an autobiographic book that Covington wrote that included many historical figures in chess and draughts. Ironically, Harris did not remember that tournament but seemed to have fond memories of military chess.

After his honorable discharge, he enrolled in UCLA, where he studied physics. Interestingly, he met Frank Street, who was also at UCLA, but studying mathematics! Street recalls having many conversations with Harris during these times but added that they were not chess-related. Street said that their discussions were about high-level subjects like science, mathematics, and physics. Harris would later enroll at the University of California-Berkley and earn a Master’s in physics.

Harris made such an impression that players would seek him out. Daniel Van Arsdale wrote The Chess Drum, and recounted the following story:

Pursuing some memories, I happened to search “Walter Harris chess” on Google. I found your interesting WWW page on Black Chess masters. I was a math major at UCLA from 1963-67, and used to play a lot of chess (once had a 2137 USCF rating). I had read about Harris, and once he showed up at UCLA, at a room where the chess was played. Someone told me (later) who he was, and we played a five minute game. I just happened to win the first game, but Harris slaughtered me in the remaining games, about 15 as I recall!

Daniel Van Arsdale, “Remembering Water Harris,” The Chess Drum, 17 November 2004

After 40 Years, Harris reunites with chess!

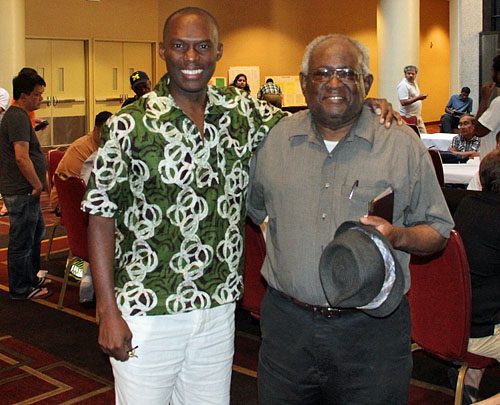

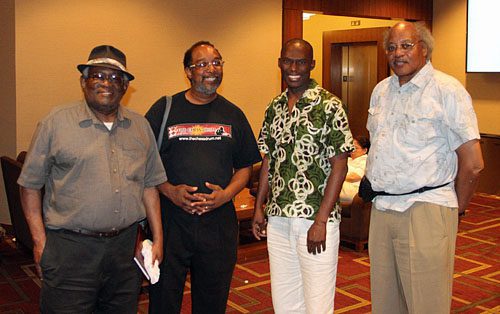

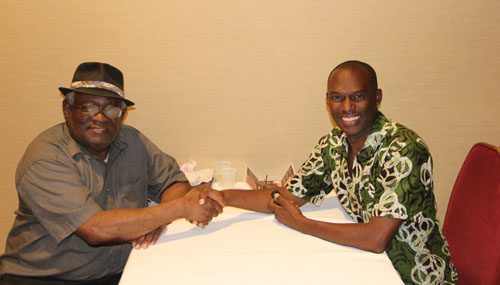

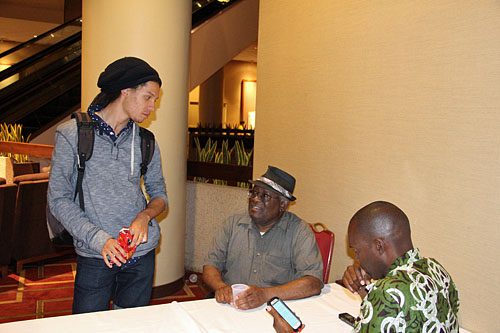

As destiny would have it, the 2014 World Open would be held in Arlington, Virginia. I contacted Mr. Harris and told him about the event and invited him to come so we could finally meet. Unlike Frank Street, Harris did not keep up with the current trends in chess but spent time volunteering as a chess teacher. He had not visited a tournament in decades. When he arrived, he called me from his cell phone. I saw him come down the escalator and went over to greet him. We finally met.

Photos by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

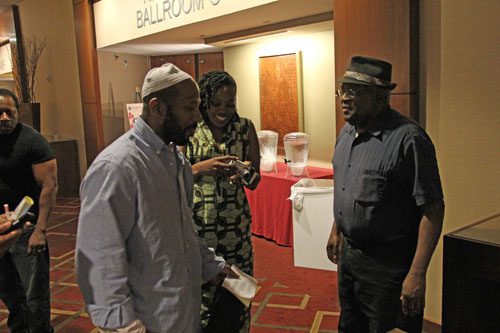

Harris would spend the next two days meeting old friends, including Frank Street, Larry Gilden, and Fischer biographer Frank Brady. He seemed to be very happy and enjoying the moment. On the second day, he returned, and I called Maurice Ashley. In previous discussions, Harris mentioned how proud he was of Ashley. I gave the phone to Harris, after which they enjoyed a cordial chat. What a historic moment!

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Over 100 Black chess players have followed Harris in earning the National Master title, with only two becoming International Grandmasters (Maurice Ashley and Brewington Hardaway). Given the low engagement in the Black community, it sometimes takes an icon to pique interest. Harris stated that there were no other master-level Black players on the American scene in the 50s.

Of course, 19th-century problemist Theophilus Thompson had long preceded Harris. In the 60s, Harris was followed by Street, Leroy (Jackson) Muhammad, and Clayton. The masters to come were products of the “Fischer Boom,” most earning titles in the 70s and 80s. Harris had already left the tournament scene, but his print was still there.

Never Forgotten

Finding out about the loss of a chess player is always a bitter pill to swallow. Particularly in the area of chess journalism and documentation, it carries a bit of a sting because the words written exemplify finality. I enjoyed my interactions with Mr. Harris, and he was always kind and in good spirits. The last interaction was when I gave him the exact rating supplement his master’s rating appeared in. I also asked him his exact birthdate, which he wrote as “September 28, 1941.”

Yesterday, while talking to Frank Street, he stated he was concerned and felt something had happened to Harris because he had not heard back from him in months. Within a couple of minutes, I searched and found the notice revealing the sad news. The sadness in Street’s voice was evident, and he mentioned that Harris had suffered from a litany of ailments, including respiratory issues and diabetes. There were no details on the circumstances and cause of his death.

Here was a touching note from one of his old acquaintances…

He spent part of his childhood in a Bronx orphanage and went on to get advanced degrees in physics from UC Berkeley and to work at Lawrence Livermore Lab. In retirement, he established chess clubs in Arlington, VA, public schools and taught a science class to my daughter’s 4th grade, who sent him a 100 heart-strewn thank-you notes. He understood relativity theory and the Higgs boson.

~Melissa Holland (October 30, 2024)

When looking at the background of Walter Harris and the fact that he spent time in an orphanage, I wondered if his father fought in World War II. While he didn’t speak much about his childhood, he is an example of overcoming adversity. He remains an inspiration for how chess can lay a foundation for success in other career endeavors. In the Black community, we certainly take this as a great example, and we stand on the shoulders of such pioneers. Thank you Mr. Harris!

Following is the 2014 interview and one of his miniatures…

2014 Interview

Walter Harris (USA) – 26:10 minutes (5 July 2014)

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum