Is Hans Niemann right??

Lennart Ootes/Grand Chess Tour

Hans Niemann has been in the chess spotlight for the past three years. The infamous case involving Magnus Carlsen at the 2022 Sinquefield Cup set the world on fire. While the point of this article is not to litigate the issue or even discuss the particulars of the case, his recent comments on harnessing young American talent raise important questions. These questions have remained at the forefront of national chess federations for decades.

Niemann has made many comments in the last couple of years. At times, one can sense a tinge of bitterness in his tone as he continues to deal with the aftermath of the controversy. Some of his comments are provocative; some are rather intriguing. One would hope that readers can focus on his most recent comment about the talent landscape in American chess. It is worthy of discussion.

The rise of Indian chess talents is largely due to structural support. Anand mentors all of the top players, large companies and the government support them financially. America has no infrastructure, all of the most talented players go to Ivy leagues and quit chess. If we want…

— Hans Niemann (@HansMokeNiemann) March 10, 2025

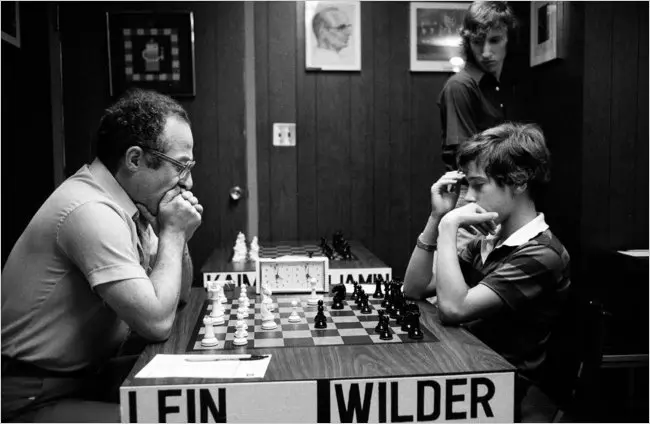

American Chess after Bobby Fischer

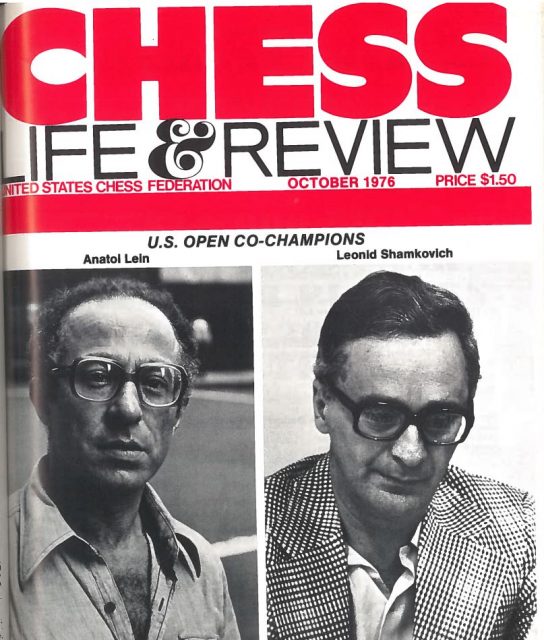

In the 1970s and 1980s, a cadre of young stars emerged in the U.S. They were products of the “Fischer Boom” resulting from Bobby Fischer’s historic win over Boris Spassky. After the fallout of this defeat, a wave of Soviet emigres began trickling into the U.S. in 1976 with Anatoly Lein and in 1979 with Lev Alburt and Leonid Shamkovich. Another player making a positive impact was Boris Kogan, who came in 1980.

(Note: Maxim Dlugy came to the U.S. from Moscow with his family at age 11 in 1977 and won World Junior in 1985.)

The chess landscape immediately changed… in a positive way. Alburt led the U.S. Olympiad team (Alburt, Yasser Seirawan, Larry Christiansen, James Tarjan, Nick deFirmian, and Shamkovich) to Malta just the following year. An early contributor to the popularity of the Benko/Volga Gambit, Alburt was a three-time U.S. Champion. After his playing days, he became a coach and trainer. These recent emigrants shared their institutional knowledge of chess.

“Americans don’t know their endgames like they should.”

~Boris Kogan, Georgia State Chess Hall-of-Fame page

During the “Fischer Boom,” players like Seirawan, Christiansen, deFirmian, and John Fedorowicz became the new stars of American chess. Let’s not forget to mention players like Mark Diesen, who won the 1976 World Junior Championship. Seirawan won World Junior in 1979. Fedorowicz mentioned in an interview at this site that during his time as a young master, the U.S. Junior Championship was stronger than the World Junior Championship.

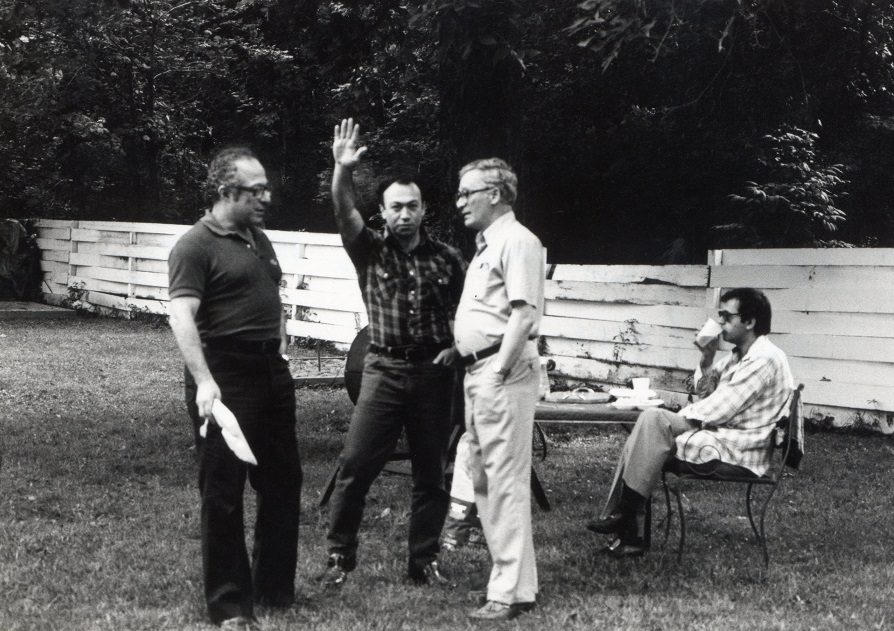

Photo by Dan Mayes

Despite showing promise, players like Diesen and Regan went the academic route. Most of the alumni from this tournament earned the GM title and stayed on the periphery of chess. However, the arrival of the contingent of Soviet players meant that these players would have to make substantial improvements in their chess understanding. There were limited resources in place for this post-Fischer generation, so they would also need to do so on their own.

Many opted to live abroad. Christiansen, Fedorowicz, and deFirmian lived in Europe for periods of time. Fedorowicz speaks of these times with a deep fondness and emphasizes how tournament conditions differed from the U.S. Despite gaining valuable experience at strong tournaments, all would return to the U.S. and continue building on what would become Hall-of-Fame careers. Seirawan competed extensively in the European circuit, participating in high-profile tournaments (including Interzonals) and seriously contended in the world championship cycle.

Up-and-coming players like Joel Benjamin, Michael Wilder, Stuart Rachels, and Patrick Wolff would represent the next wave of talent. All won the U.S. crown, with Benjamin winning in 1987, 1997, and 2000, Wilder in 1988, Rachels in 1989, and Wolff in 1992 and 1995. However, of the four, only Benjamin made a career of chess. During the 1990s, another wave of immigrants came to the U.S. after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990-1991.

Benjamin continued as a strong Grandmaster and enjoyed tremendous national success (as player and author), but never made a deep run for the world championship. Wilder became a lawyer, Rachels a philosophy professor, and Wolff went on to manage a hedge fund started by Peter Thiel, once a talented young player in his own right. It becomes evident that chess is an excellent platform for academic and career success.

Immigrants Change Chess Landscape

In the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, the U.S. did not have many FIDE-rated tournaments, and players had to settle for the swashbuckling Swiss-style opens. As the immigrants began to dominate the opens, much of the American talent could not keep up with the talent influx. Phenom Gata Kamsky arrived from the Soviet Union with his father, Rustam Kamsky, in 1989. While Michael Wilder had no illusions of being a full-time player, Patrick Wolff tested the waters before graduating from Yale and coming to the following realization:

“I had to ask myself if this was what I wanted to do for the next umpteen years. And basically it was the opportunity cost. The longer that this went on, the more difficult it would be to switch to something else.”

~Patrick Wolff in New York Times June 12th 2010

Many young talents found it challenging to make the talent jump, and many of the U.S. championships in the 90s were loaded with immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Naturally, they started to dominate spots on the U.S. Olympiad team. Some federations were accused of farming players from the various Soviet republics.

A running joke at Olympiad tournaments became

Question: What do you think of the Russian team?

Answer: Which one?

The joke was primarily aimed at the U.S. and Israel, which were comprised of players who had left the Soviet Union for better opportunities. This had an effect. In one situation, 16-year-old Hikaru Nakamura was left off the 2004 Olympiad team. The U.S. team is comprised of Gregory Kaidanov (2749 USCF, 2621 FIDE), Alexander Goldin (2712 USCF 2624 FIDE), Igor Novikov (2708 USCF 2610 FIDE), Alexander Onischuk (2706 USCF 2655 FIDE), Alexander Shabalov (2674 USCF 2605 FIDE), and Boris Gulko (2705 USCF 2600 FIDE).

Nakamura was 2666 USCF and 2601 FIDE. Gulko was largely inactive, but the U.S. Chess Federation used national ratings (as of April 2003) to determine the team. The young phenom was on the outside looking in, and that 2004 team placed 4th in Calvià, Spain. They had come in 41st in the previous Olympiad, so it was a relative improvement, but something had to be done. Nakamura’s talent could not be denied. To accentuate the point, he won the 2005 U.S. Championship.

(Note: The tournament was played in 2004 and was post-dated for legal reasons.)

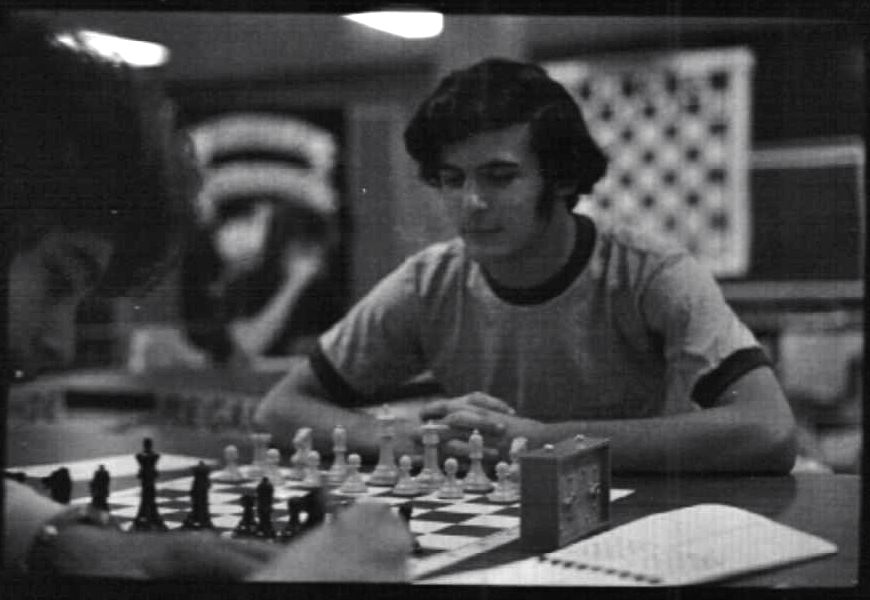

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

We ran an article about Nakamura’s Olympiad snub and why it was bad for chess. We also ran one on why his first U.S. Championship was good for chess. In speaking with The Chess Drum, Nakamura stated in subsequent conversations that he didn’t fit in with the foreign players, and it was hard to trust them.

Nakamura had become a serious threat to the system and eventually climbed the FIDE rating chart despite his reputation as a blitz specialist. He received initial training from his stepdad, FM Sunil Weeramantry, but he had no professional trainer. He later enlisted the services of data analytics expert Kris Littlejohn and began to prove he was the ‘real deal.’

Chess for Success

Legendary Grandmaster Maurice Ashley once stated, “Chess can take you far… just not in chess.” In fact, Ashley was one of the first to understand that playing chess full-time in the U.S. was economically infeasible. He cobbled together a Hall-of-Fame career covering practically every activity in chess: player, coach, trainer, author, public speaker, commentator, streamer, and organizer. His latest project is a foundation to develop talent in the African-American community.

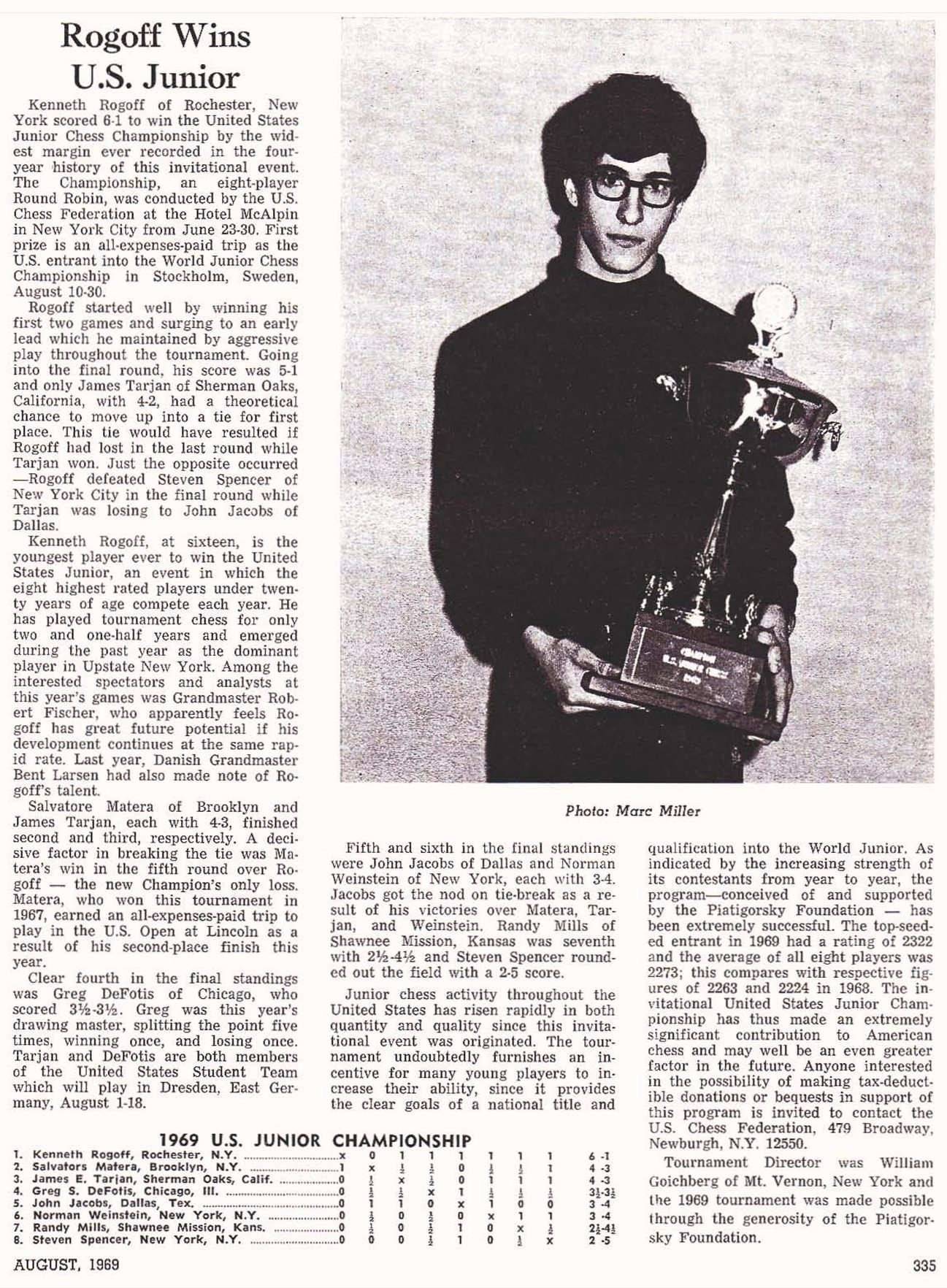

Many players use chess as a platform because it looks terrific on their college applications and resumes. There are some practical lessons to learn from many successful professionals who have chess in their background. However, with so much talent, why did these players not pursue chess? Kenneth Rogoff, a prominent American economist, did choose chess initially, even dropping out of high school!

After winning the 1969 U.S. Junior, he lived in Europe for several years because there were more chess opportunities. However, he returned to the U.S. at age 18 and decided to pursue academics at Yale. He is now a distinguished professor at Harvard and has continued to extol the virtues of chess.

Imagine how difficult it may be to pick up one’s life and move away from home at such a young age. Given the lack of national support, that is what many talented chess players from the U.S. had to do. Abhimanyu Mishra and his father traveled to Europe and vowed not to return until he had achieved his goal of becoming the youngest Grandmaster in history. Mishra still holds the record.

With the emergence of the St. Louis Chess Club and the Charlotte Chess Club, there are more norm opportunities, but not enough. Of course, Bill Goichberg’s tournaments are still a mainstay of the American chess diet, but they lack reasonable norm conditions. In addition, those who visit the U.S. and play in these tournaments often say they are not up to international standards.

The argument is that European conditions are more favorable, but staying for extended periods is expensive. To Goichberg’s credit, his tournaments have provided an arena for all emerging players, including Nakamura, Caruana, Shankland, Robson, Xiong, Sevian, and Niemann. All have made 2700 FIDE growing up on American-style tournaments.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

While the above players have excelled at chess, how will players like Robson, Sevian, and Niemann proceed? Robson is now 30 and seems to be deciding on a career path. Sevian is active and appears dedicated to chess, and Niemann (at #20 on the FIDE list) has a strong ambition of being a world champion. While 16-year-old Mishra seems to be laser-focused on improving, Liang will be graduating from the University of Chicago in May and has to make a critical decision.

The Fork

In the 80s and 90s, American talents struggled in open tournaments, while the immigrants (many seasoned players) often assisted each other and moved ahead. The point is not to blame the immigrants for excelling in their adopted nations but to point out the lack of national resolve to support promising chess talent. Yes, there is the Samford Fellowship given to promising players, but there was still a lack of an ecosystem to promote professional chess.

One effect of the wave of immigrants from the 1980s and 90s is that 30 years later, many of these players are now trainers. As a result of this access to training, a wave of young U.S. talent has emerged. Nevertheless, promising chess players generally face a “fork in the road.” The most famous case involving a top American player may be Fabiano Caruana, who left for Europe to seek training and strong FIDE tournaments. He returned in 2015 with his GM title and #2 in the world rankings.

Regarding the U.S. Chess Federation’s role, the organization has always had limited resources for talent development and the professional class. When the federation struggled to host the U.S. Championship, St. Louis philanthropist and chess enthusiast Rex Sinquefield stepped in. He opened the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of St. Louis in 2008 and hosted the U.S. Championship in 2009. The first Sinquefield Cup was held in 2013 with four players: Magnus Carlsen, Hikaru Nakamura, Levon Aronian, and Gata Kamsky.

This filled a tremendous void and gave young players hope as they watched elite players battle in their country. A number of young players moved to St. Louis to gain access to a competitive and professional environment. The other factor was Susan Polgar moving her SPICE program from Texas Tech to Webster. This served as a catalyst for other competitive chess programs in St. Louis. In less than a decade, St. Louis became the center of chess and is now home to the World Chess Hall of Fame. In 2022, The U.S. Chess Executive Board voted to move the U.S. Chess Federation headquarters to the city.

So much conversation has been had about harnessing talent, especially in the U.S. The talent trend has undoubtedly been shifting east toward Asia, as China, India, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan represent countries that have produced a wealth of young talent. In India, both the private and public sectors are fully supportive of chess. With a national hero like Viswanathan Anand serving as marketing ambassador, the results have shown how vital national support can be.

Is the U.S. Playing “Catch-up”?

U.S. Chess has its claim to several rising talents, but young players are often confronted with the challenge of how much time to invest in chess. The incentive for spending hours on chess is a substantial opportunity cost compared to focusing on one’s academic endeavors and career aspirations. There is significantly more to gain from a career in finance, computer science, medicine, or business than in chess, as the U.S. has a lot of economic opportunities.

Hikaru Nakamura recently gave an interview in which he spoke of how the U.S. is trailing in the talent race. Niemann, who did a video reaction, had posted on X.com that many talented players use chess as a platform, attend elite schools, and quit chess. Is this true? We can point to many cases, but it also includes many success stories.

We may not like the anecdotal evidence that Niemann is presenting, but it doesn’t take a funded research study to see that the American talent spigot will run dry if the structure is not fixed. American juniors dream of being on the Olympiad team to represent their country. However, if younger players continue to see foreign arrivals leapfrog onto the national team, what incentive will they have to spend the time needed to climb the ranks?

Photo by Michal Walusza!

The U.S. was criticized for farming top boards from other federations. The argument lacks context. Although Caruana represented Italy for 10 years, he was born in Miami, raised in Brooklyn, and spent his early years representing the U.S. Wesley So came from the Philippines as an international student to study at Webster University and pursue chess goals. He also became a U.S. citizen in 2021. The 2016 gold medal team was more American than any team since the time Bobby Fischer played with Pal Benko.

(Note: Another important player was Lubomir Kavalek, who defected from Czechoslovakia in 1970, was one of Fischer’s seconds in Reykjavik, and played with him on the Olympiad team starting in 1972. Kavalek went on to have an illustrious career and coached several U.S. juniors, including Mark Diesen and Yasser Seirawan.)

As we have seen in other sports, the building of “superteams” is unsustainable. In 5-10 years, the U.S. may have a tremendous talent void. Strong talents may decide that if chess entities continue to invest in top foreign imports, they will focus on university studies and careers. There is irrefutable proof that chess can be a platform for academic and career success. Niemann suggests more investments should be made in local talents before they hit the fork in the road.

Niemann pointed out that India, China, and Uzbekistan develop their talent organically, which makes for sustained progress that everyone can see. India and China were not in the top 20 in the world 30 years ago, but you can see that they were developing a culture. With the presence of Viswanathan Anand, it became a national obsession to raise the next generation of chess talents to succeed him. Anand personally had a direct hand in this process, and India has built a structure that has produced 85 Grandmasters in less than 40 years.

Both teams had already received their gold medals.

Photo by Maria Emelianova

In China, they had training cohorts, and national coach Ye Jiangchuan led the charge with the help of government backing. The National Chess Center in Beijing, managed by the Chinese Chess Association, is mind-blowing. There was an agenda to produce a chess powerhouse, and these developments produced an unprecedented eight 2700-level players in less than twenty years (starting with Wang Yue, Bu Xiangzhi and Ni Hua). These developments were noted on these pages as early as 2001. Everyone can see the result, but it took time to get the engine going.

Is the U.S. Squandering Chess Talent?

Let’s take a closer look at the decline of American chess. Players like Caruana, Aronian, Dominguez, and So originally represented other countries, and their transfers were largely driven by financial incentives. Meanwhile, homegrown talents like myself and Mishra receive minimal…

— Hans Niemann (@HansMokeNiemann) March 12, 2025

While Niemann’s message is rather provocative, he is alluding to the fact that the U.S. has had instances of immigrants coming and taking would-be positions of rising stars. Hans was born in Hawaii, spent part of his childhood in the Netherlands, and spent his formative years in San Francisco. Now based in Connecticut, he has traveled the world looking for opportunities to play top-level chess. He is fully vested in chess as a career and wants to compete at the highest level.

More recently, he posted the above messages on X.com (Twitter). While Niemann will not win any style points for his messages, several of his points were interesting and should be taken with the utmost seriousness. They point to a problem the U.S. has had for the past 50 years. How do you nurture American talent at home? Fabiano Caruana (mentioned in the posts) was born in the U.S. but had to leave the country to find better training and norm opportunities in Europe.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

The U.S. chess environment had been stagnant and was dominated by the open tournament scene, where norms are exceedingly difficult to earn. Caruana sought training and ended up living in Hungary, Spain, and Switzerland during his 10-year sojourn. He also represented Italy in several Olympiad tournaments before returning to the U.S. Many in the chess world did not realize he was born in the U.S. and credited Italy with developing him. In one interview, he was even asked how he spoke such good English!

The other players came under very different circumstances, as Wesley So was recruited by Susan Polgar to attend Webster University. After attending Webster for two-and-a-half years, So decided to focus on chess full-time after winning the 2014 Millionaire Chess Open. If you look at Hikaru Nakamura, Fabiano Caruana, Sam Shankland, and Ray Robson (who won an Olympiad gold medal together), all are American products but reached 2700 in very different ways. Shankland was public about his frustrations and was close to giving up chess. After winning the 2010 U.S. Junior, he decided to work incredibly hard and eclipsed 2700. Shankland won Olympiad gold (individual) in 2014 and Olympiad gold (team) in 2016.

The current crop of players, such as Hans Niemann, Sam Sevian, Awonder Liang, Andy Woodward, and Abhimanyu Mishra, are top juniors but are in an era where continual improvement is required. Looking at India, they have Dommaraju Gukesh, a world champion at age 18. Their 2026 Olympiad team in Uzbekistan will probably average less than 21 years. On the other hand, the U.S. team in the 2024 Budapest Olympiad had Ray Robson as its youngest player. He is now 30, and his rating has been stable for the past 10 years (2680 in 2015 and 2689 in 2025), peaking at 2704.

If we look at the field from the 2015 U.S. Junior Closed.

- IM Jeffery Xiong (2606)

- IM Akshat Chandra (2589)

- FM Michael Bodek (2527)

- IM Luke Harmon-Vellotti (2526)

- FM Ruifeng Li (2502)

- IM Yian Liou (2501)

- FM Arthur Shen (2477)

- NM Mika Brattain (2457)

- FM Awonder Liang (2428)

- NM Curran Han (2211)

Where are they now? Looking at their FIDE progress charts and online activities, only Xiong, Chandra, and Liang (now Grandmasters) continued to pursue higher levels of chess. Thirty percent is actually not a bad number. However, we also need to look further.

Jeffery Xiong won the World Junior in 2016, and he reached his peak rating of 2712 in 2019. Now 24, he stands at 2636 but never played for the U.S. Olympiad team. Awonder Liang is still making progress but remains outside of the Olympiad team. Liang will be graduating from the University of Chicago in May, and it remains to be seen whether he will pursue chess professionally. Akshat Chandra earned two degrees at St. Louis University, including a Master’s in Philosophy last year. He is currently a full-time coach/trainer. His peak FIDE rating was 2563 in 2021. He is now 2463.

While these three young Grandmasters will do well in life, what may have been their future if there was an ecosystem in place to harness their talents?

The Tough Question

It is strange to see a legendary name like Larry Christiansen still in the top 20, but perhaps that shows problems with the attrition rate. Niemann made another suggestion. If veteran foreign players are brought in, part of the requirement would be to train the next generation. He also mentioned that promising American talents should be offered financial incentives to focus on chess. This is necessary because a talented American chess player must make an important decision.

In the U.S., there is a rich chess history but no definable chess culture. American players have continued to find success, but much of it is through their determination and will. There are many scholastic tournaments for junior players, and Super-Nationals still draw over 5,000 players. Once these junior players began to consider colleges, there was another reality.

Most of the players at the universities with well-funded chess programs are international students. To pursue chess, should a talented junior attend one of the powerful chess programs and compete for a slot, or attend another American university without a chess training program and focus on social development and academics? This is a reality.

One project that attempted to establish a professional circuit was the Millionaire Chess franchise. Maurice Ashley tried to create a series of tournaments that offered lucrative prize funds. The idea was novel, but it was not sustainable. Long-standing sponsorships are needed for these activities. Unfortunately, chess has not attracted the type of sponsorship worthy of its reputation.

It may very well be that U.S. Chess and its stakeholders have to write a strategic marketing plan to position chess and make it more attractive. Without relationships with consistent sponsors, chess will continue to languish, and players will choose to abandon it for more lucrative opportunities.

Niemman suggests that sponsors can offer someone like Awonder Liang $100,000/year to focus on chess. It may very well be that US corporations can put qualified players on the payroll. We see Indian corporations doing this with all of the top players. India’s model was 40 years in the making, but they have a charismatic figure in Viswanathan Anand. Who will be that person for the U.S.? Following is the video reaction from Hans Niemann on comments Nakamura made about the future of American chess. It’s a must-see!

Video by chess.com

Chess Renaissance

Let’s be clear. Foreign players coming to the U.S. can be a good thing. However, there should be some caution to avoid discouraging young players who have been training for years to represent their country. If the top juniors continue to see foreign players immigrating to the U.S., immediately getting conditions and spots on the national team, it sends a conflicted message.

The parents of young players have invested a lot in the U.S. chess infrastructure, supported tournaments, spent thousands on chess education, and have a vested interest in the success of U.S. Chess. Parents and juniors need to see that the fruit of their investments can possibly be reaped as they aspire to make their national team. Seeing a player on the Olympiad team with whom they have no memory as a participant in the system is a bit dispiriting.

Niemann suggests that top players switching federations should help train the next generation of players. These players have a wealth of knowledge, and it may be their way of contributing to American chess. In the past, players from the former Soviet Union shared their training insights with America’s juniors. Perhaps we need a more formal structure where the current group of foreign players can help build the chess infrastructure in the U.S.

Photo by Peter Doggers

An esteemed player like Levon Aronian may have ideas about how to build a sustainable chess culture. Before the withdrawal of support for chess, Armenia had built an enviable culture, resulting in three Olympiad gold medals. Leinier Dominguez may have insight into how chess maintains public acceptance in Cuba.

Chess TV in Havana, Cuba

Despite the lack of support for professional players, chess can literally be seen everywhere in Cuba, including on daily TV programs. The Hotel Habana Libre still has photos on its walls from the 1966 Olympiad held in Havana. Have these elite players been brought before the U.S. Chess Executive Board for a debriefing?

St. Louis has built the ecosystem with an elite campus, a World Hall of Fame, local GM talent from universities, and the U.S. Chess headquarters. IM Carissa Yip is graduating from Stanford this spring and will be relocating to St. Louis to pursue the Grandmaster title… and the $100,000 Cairns prize. This is an incentive for U.S. citizens to earn the coveted GM title.

Eligibility will be limited to female chess players who are American Citizens or become American Citizens before earning the rank of grandmaster.

~St. Louis Chess Club

Photo by Stev Bonhage

Investing in American talent is precisely the idea Niemann mentioned.

One reality is the overreliance on St. Louis to push the chess agenda. Nakamura made a very insightful point: What happens after Rex Sinquefield decides to retire? There may be other wealthy patrons of chess, but it is doubtful to find a benefactor who loves chess as much as Sinquefield. Even replacing Bill Goichberg would be incredibly difficult. The reality is that the U.S. chess community needs to develop a contingency plan and focus on cultivating its chess talent… before it’s too late.

As someone who lived in public housing as a teenager, I appreciate the opportunities that chess has given me. But I also realize that chess is a game. For most young American GMs, going to university makes more sense than pursuing a professional chess career.

Young Indian GMs may simply have fewer promising non-chess options.

That’s very true. They can go into the tech sector, but it’s so competitive. There are thousands of professionals for every available position.

The other thing about the U.S. is chess is still on the fringes amidst all of the other leisure activities available. People still know Bobby Fischer, but we have done a horrible job of marketing chess. In contrast, India has done a fantastic job at making chess a thing of national pride.

A lot of important points made here. The first and most important step is to provide a robust and viable alternative to CCA tournaments. They are run as if it’s still 1985. Portable bulletin boards with inscrutably long blocks of text. Arbiters and TDs approaching senility who are completely checked out. Max of one or two DGT boards that are guaranteed to malfunction at least once during the tournament. And virtually no norm chances.

All facts. These things have been pointed out for a long time. Of course, CCA is a private organization, but a very important one. It does need reform since it provides our young players with access to strong players. They need to have an idea of what a professional environment looks like. CCA tournaments are primarily organized for chess hobbyists and weekenders. You will not find many elite players at a World Open anymore.

Dear Daaim,

Wonderful article. Congratulations! Just a factual correction. You wrote:

“The first Sinquefield Cup was held in 2013 with four players: Magnus Carlsen, Fabiano Caruana, Levon Aronian, and Wesley So.” The first Sinquefield Cup featured Magnus, Hikaru, Levon and Gata Kamsky.

Please. Keep up the insightful commentary.

Kindly,

Yasser Seirawan

I thought I remembered Gata and Aronian, because I was there. I checked one reference and I’m not sure how I got that one wrong. Going too fast!

Thanks Yasser!